Why has Rebecca always had a reputation as a queer novel?

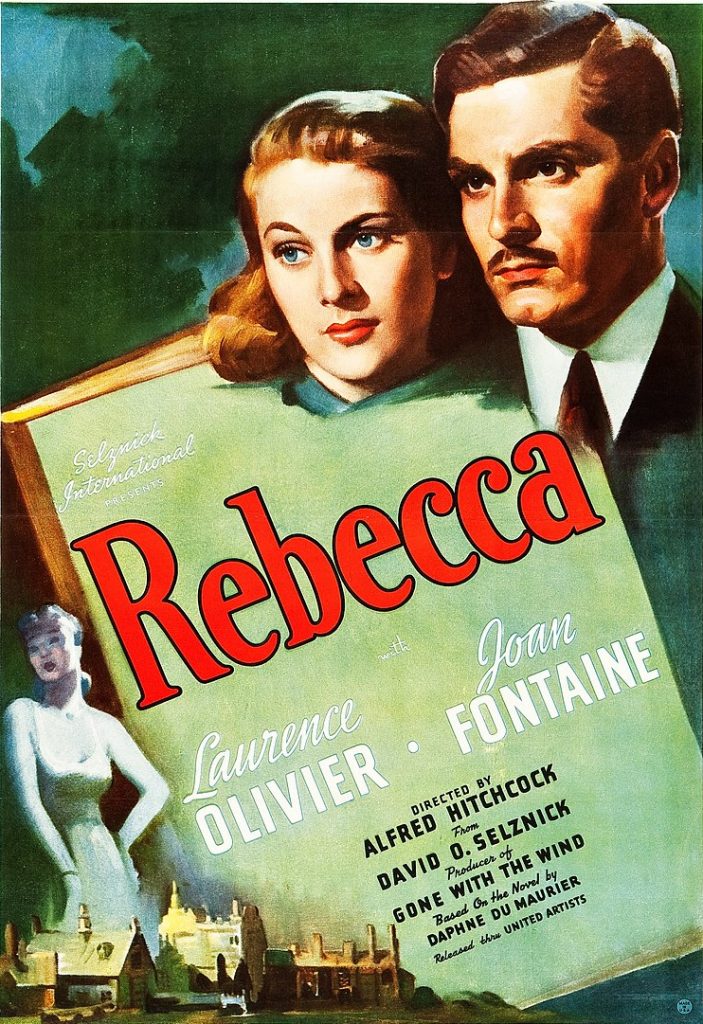

Generations of gay men have declaimed the first line, spoken by Joan Fontaine in the 1940 film: ‘Last night I dreamt I went to Manderley again’. But for most of its 82 years in print, critics dismissed it as an ordinary gothic romance.

It has a mysterious mansion, an innocent heroine, an enigmatic hero, a beautiful dead first wife, a sinister housekeeper, and a faithful dog. The heroine is haunted by the first wife and nearly kills herself. But she and the hero end up together.

Still, there was something more going on.

I know when I decided that Rebecca was a queer novel. It was in 1977, when I heard Antonia Fraser (biographer of Mary Queen of Scots and Oliver Cromwell) and writer Daphne du Maurier go head to head about Rebecca on Radio 3. I remember the programme because I had just come to the UK and discovered Radio 3, and found it fascinating.

Fraser took part in the programme because she found Rebecca fascinating. She had named her eldest daughter for the beautiful and compelling title character. She had become so involved with the story that she decided to rewrite it from Rebecca’s point of view.

In the original story, Rebecca, mistress of Manderley, dies one night in a sailing accident. Everyone (it seems) mourns the loss of such a graceful, spirited, kindly person. Maxim, her widower, marries a naïve young woman, a heroine whose name we are never told. One of life’s lurkers, shy and undistinguished, she wonders endlessly about Rebecca.

Halfway through the action, Maxim reveals that Rebecca’s good qualities were a sham. In reality she was a manipulator and a liar. She enjoyed acting the part of the lady of Manderley while pursuing a hedonistic life in London. She was incapable of love, he insists: ‘she was not even normal’. When she threatened him in her cottage on the beach, he killed her and sank her boat to make it look like an accident.

Fraser wanted to believe that Rebecca was ‘really’ kind and lovely, and that Maxim was the liar. She was reading the novel as young people and fans sometimes do: as a participant, not a spectator.

Du Maurier listened politely to Fraser’s rewritten version of her story. Then she said that, yes, she had to wonder if she had gotten Rebecca completely wrong. But she felt that meddling in other writers’ work could lead in strange directions. As it so happened, she had been doing research into the life of Charles the First, and discovered a manuscript describing his affair with Oliver Cromwell. She said she had no plans to publish this startling revelation, but hoped Fraser would take it as a friendly warning.

Many people must have listened to this talk, and some of them may have wondered about it afterwards. Du Maurier had warned Fraser off elegantly and made her look a bit naïve. (Fraser didn’t seem offended. Her alternative Rebecca story and du Maurier’s riposte were later republished together.) But why had du Maurier used such a daring fantasy to make her point – a fantasy which was a bit beyond the pale? In the 1970s, talking about queer kings at all was pushing the boundaries.

I wondered if there was a covert message in du Maurier’s talk and remembered the line about Rebecca as a woman who could not love; ‘she was not evennormal.’ Not even normal? Were her lovers not normal, or was her attraction to them not normal – because some of them were women?

Maxim also says that Rebecca told him terrible things about herself, things he would never repeat to anyone. What could they have been? Rebecca probably had not told him she was the leader of a Satanic cult or a serial murderer. The phrase was much more likely to mean that she boasted of her sordid affairs with both sexes and that he realised she was one of those ‘reptile women’ who could not feel love, only unnatural lust.

The idea that a book as famous as Rebecca, which had been in print for 39 years at that point, could be ‘a gay novel’ was tremendously exciting. Just four years earlier, Vita Sackville-West’s autobiography had been published. It revealed that Orlando was Virginia Woolf’s love letter to Vita. Little by little, queer dimensions in writing were emerging. (These days, we even hear that Charles the First may have been attracted to his father’s lover, the Duke of Buckingham.)

Du Maurier herself insisted that Rebecca was not a romance. She called it ‘a study in jealousy’. The most overtly jealous character is the housekeeper, Mrs Danvers. She is ‘devoted’ to Rebecca, who called her ‘Danny’. She tells anyone who will listen about Rebecca’s courage, distinction, riding skills, taste in clothes. In one of the novel’s most famous scenes, brilliantly translated to the screen in Hitchcock’s film, she shows the heroine Rebecca’s evening clothes, her nightdress and her bed, encouraging her to touch the satin and put her face against the furs. She is a camp figure, exaggeratedly grim and stark, but for most readers, just a sinister sideline in a story of jealousy in marriage.

But after du Maurier died in 1989, her biographers were able to be truthful about her life. It emerged that she was bisexual and had fallen in love with her publisher’s elegant wife, Ellen Doubleday. She had also had an affair with the actress Gertrude Lawrence (though Lawrence’s family deny the idea to this day).

In letters, du Maurier compared Doubleday to Rebecca, seemingly embracing her vision of Rebecca’s beauty and charisma and discarding the dark side. Perhaps du Maurier herself, through her passion for Doubleday, had come to see Rebecca differently.

Du Maurier’s death left other writers free to ignore the warning she gave to Fraser. (In modern publishing, with its publisher-commissioned prequels and sequels, being involved with other writers’ works is not just a temptation, it’s good business.) Sally Beauman, journalist and critic, published Rebecca’s Tale in 2001. It portrays Rebecca as adventurous, romantic, ruthless – and, marginally, bisexual. Meanwhile, one of the characters, her brother, turns out to be gay.

The character of Mrs Danvers – rarely explored in writing – has grown and changed in film and on the stage. Portrayed by powerful actresses such as Judith Anderson, Diana Rigg and Anna Massey, she is no longer the grotesque figure in the novel. In Rebecca, Das Musical, Susan Rigava-Dumas portrays her as darkly beautiful and vital, almost an avatar of Rebecca herself.

This comes closest, perhaps, to a queer reading of du Maurier’s novel. Mrs Danvers, who loved Rebecca, becomes her voice in the world of the living and holds onto her claim to Manderley. But all the major characters, not just Rebecca or Mrs Danvers, could be described as misfits in the world of patriarchy. They are people who don’t belong, sexually and in other ways. It is a novel about three women fighting over a house (and over a man because he brings them a place in that house). Manderley is more than just a mansion – it is the characters’ only chance at a life or a home.

Our views of Rebecca will keep unfolding as queer culture becomes more insightful, as boundaries are rethought, challenged and broken down.

Rebecca has been in print ever since it was published in 1938. Lavender Menace Queer Books Archive has a copy of the Virago edition.

Leave a Reply