Category: Blog

-

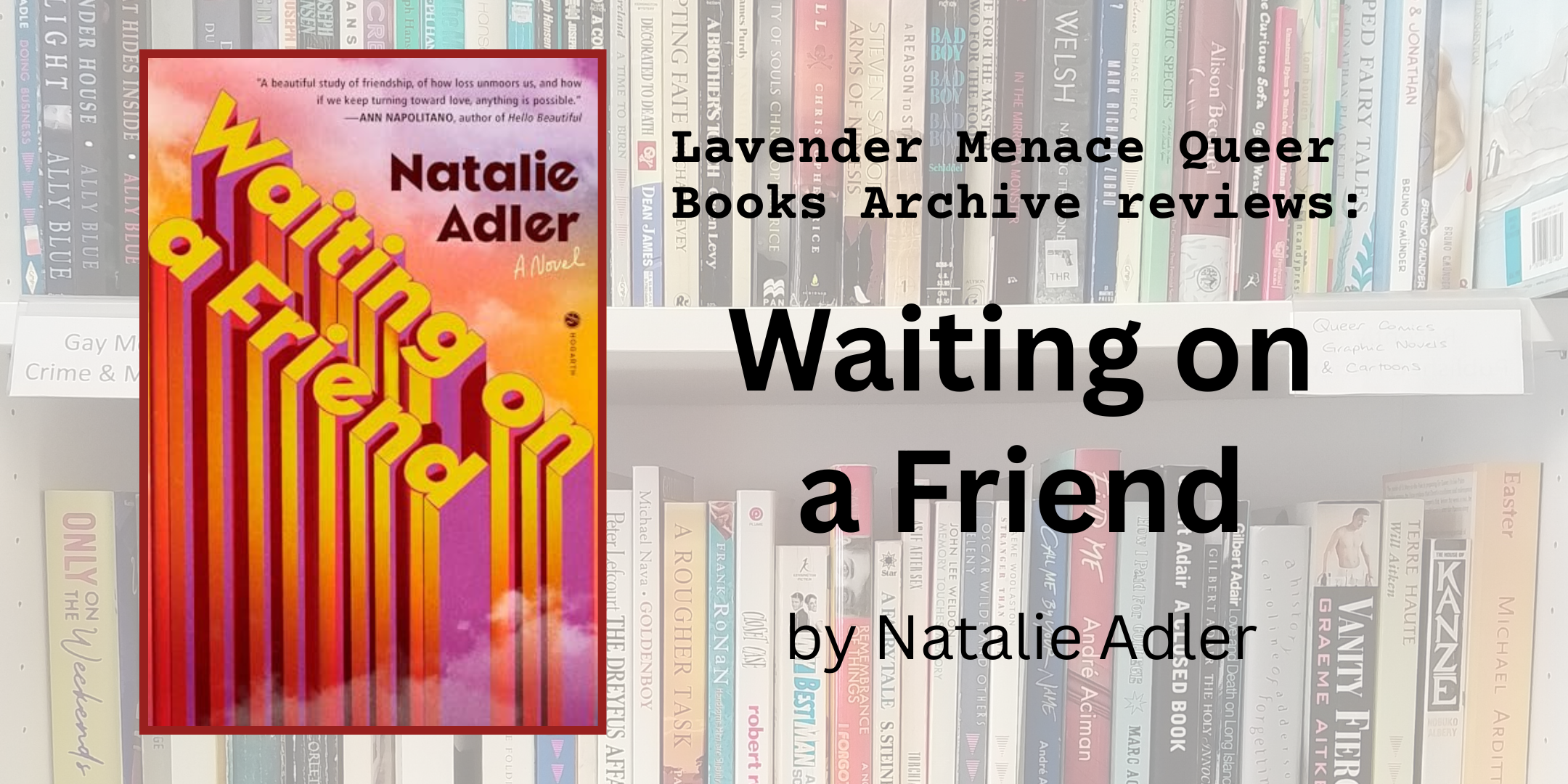

Book Review: Waiting on a Friend by Natalie Adler

Lavender Menace volunteer Katie Marson reviews Waiting on a Friend by Natalie Adler, which will be published by Quercus Publishing later this year. Natalie Adler’s Waiting on a Friend is […]

-

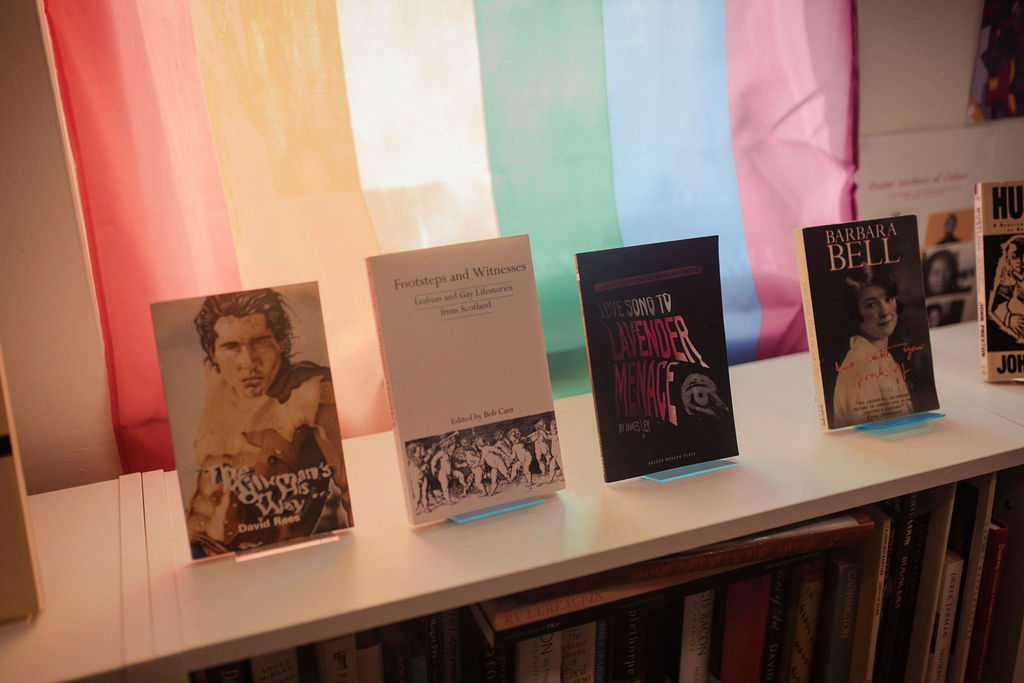

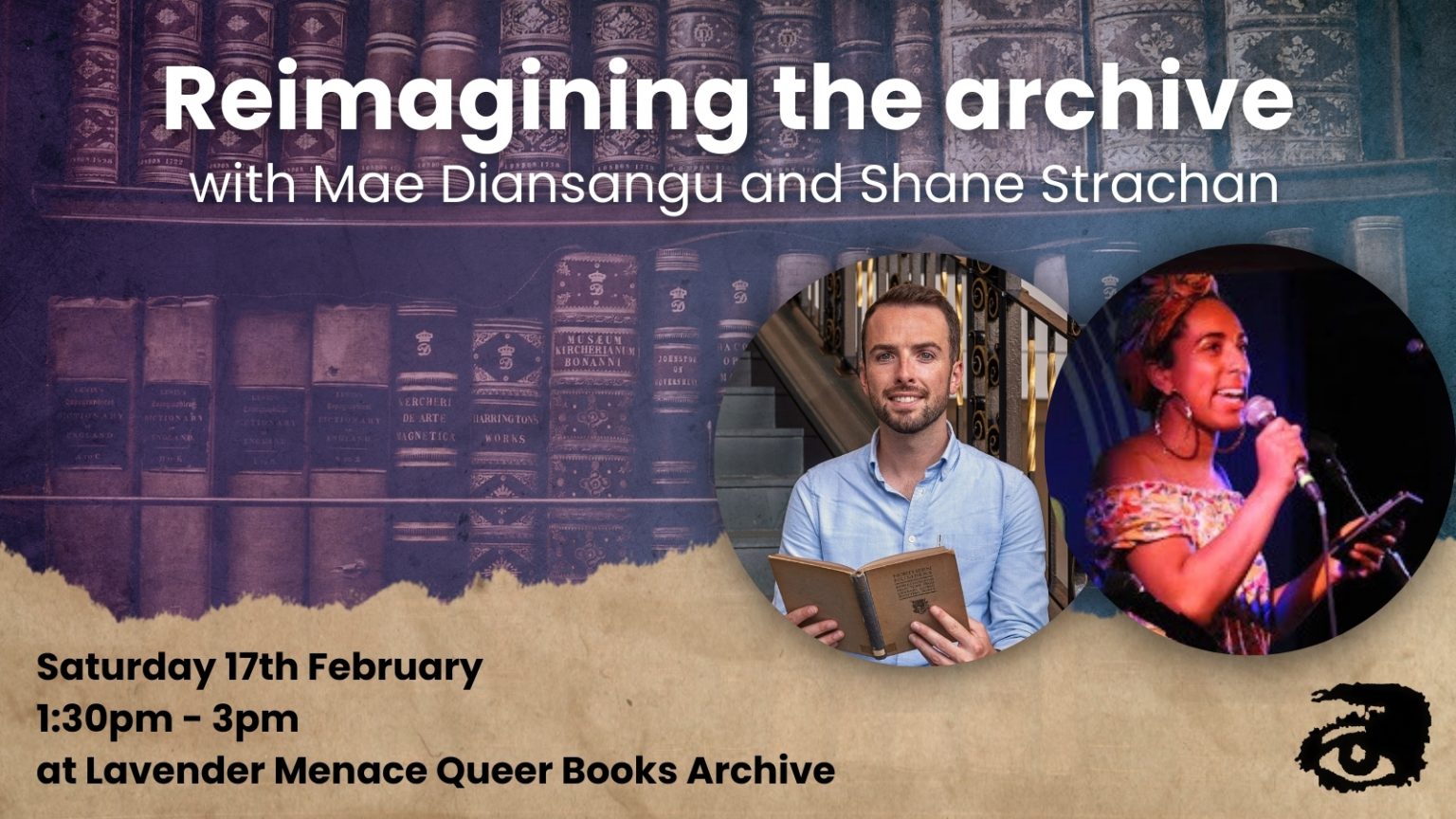

Reimagining the Archive with Mae Diansangu and Shane Strachan

You can now watch the recording of this event online Last year, we welcomed Mae Diansangu and Shane Strachan to the Lavender Menace Queer Books Archive for an afternoon of […]

-

Archiving Queer Futures: Eman Abdelhadi in conversation with Nat Raha

You can now watch the recording of this event online. Lavender Menace hosted an online discussion between two activist scholars on imagining and archiving queer futures. Dr Eman Abdelhadi is […]

-

At the World’s End

Meggie’s Journeys by Margaret D’AmbrosioPolygon, 1987 A few days ago, #ReclaimTheseStreetsPorty, one of the groups formed after the abduction and presumed murder of Sarah Everard in London, attached a series […]