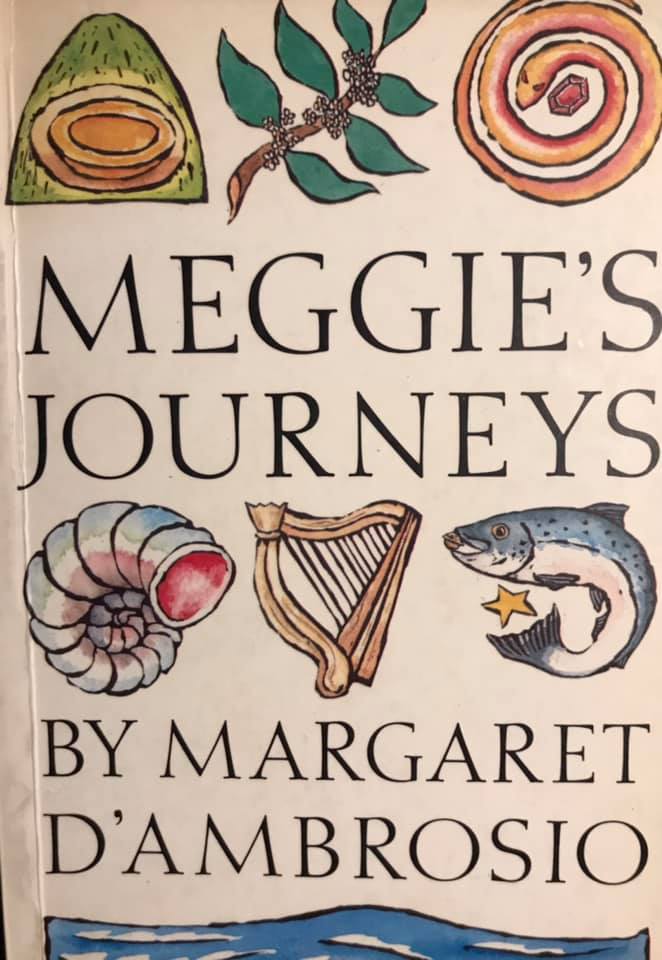

Meggie’s Journeys by Margaret D’Ambrosio

Polygon, 1987

A few days ago, #ReclaimTheseStreetsPorty, one of the groups formed after the abduction and presumed murder of Sarah Everard in London, attached a series of posters and banners to a fence at Portobello Beach in Edinburgh.

‘Our Bodies Our Minds Our Power’, said one. Others said, ‘Educate your sons.’ ‘Strong women stay strong.’ ‘Good men challenge violence in word and deed.’ ‘Be a radical dreamer.’

Many people stopped to look more closely and read a list of victims of violence against women in 2021 and 2020. Some passers-by were disturbed or confused. Others were moved by the signs.

It’s possible that no one who saw them knew the name of Margaret D’Ambrosio. She was a writer who was killed by her partner 21 years ago in Port Seton, along the coast from Portobello.

D’Ambrosio’s book, Meggie’s Journeys, has been out of print for many years (it apparently went into a second edition with a new publisher in 1988). It once sold well at the First of May Bookshop and West & Wilde. It is women’s writing rather than queer writing, except in the sense that it describes a wisdom which accepts many ways of love and of life. It is a Celtic fantasy novel of legendary times on the land which would one day be called Edinburgh. The dedication reads: To the Old Ones: Nothing is ever forgotten. We’re delighted to have a copy in our archive.

But nearly everything about D’Ambrosio’s writing seems to have been forgotten.

A search on the internet reveals much more about her death than her life. She and her partner were found in their flat on 23 January 2000: she had been murdered; he had committed suicide.

The Herald reported that she had been interested in New Age beliefs, sang in folk clubs, and had worked at the Bull and Bush pub in Lothian Road around the time her novel was published. Did she publish anything else? The paper didn’t say.

Polygon, her publisher, was the literary imprint of Edinburgh University Press at the time Meggie’s Journey first appeared. And it seems unlikely that they would have accepted D’Ambrosio’s novel unless she had a history as a writer – possibly under a different name. In 2002, Polygon became an imprint of Birlinn an independent publisher based in Edinburgh. Today, it continues to publish literary fiction and poetry by such well-known Scottish writers as Liz Lochhead and Edwin Morgan.

In 1987 Polygon had an imaginative list. Its books were sometimes found in the First of May and Lavender Menace. The cover Polygon gave D’Ambrosio’s book was beautiful and unusual, different from the primary colours usually found on radical books. It featured old-fashioned, softly coloured pen-and-ink drawings by Hazel McGlashan of Celtic symbols such as plants and animals, and at the bottom of the cover, waves on the sea.

The cover represents the book well. It is a picture of what Iron Age culture may have been like, similar to the Boudicca series by lesbian writer Manda Scott. Speaking at the Edinburgh International Book Festival, Scott said she wanted to portray a society where the sexes were equal and nature was not exploited as in modern times but considered a source of wisdom and spiritual power. D’Ambrosio’s vision seems to have been similar, but while Scott’s novels are stories of conflict, Meggie’s Journey is closer to poetry. It is meant to take us into the state of mind of her Celtic characters.

The novel explains that Celts believed in the Otherworld, similar to the Christian Heaven – but instead of being remote, it existed within nature and the world we know. In certain places and times, human beings could slip through the barriers into a truer world than our own.

In the novel, Meggie is questing for the Well at the World’s End, which will show her the face of the Goddess. On the four seasonal Celtic festivals (which include Beltane, still celebrated in Edinburgh), she journeys to the Otherworld. Her companion is Annis, sometimes an old woman, sometimes a young maiden.

Meggie meets the Sidhe, a race of spiritual beings well-known in Celtic legend. White ravens and beautiful spirits speak to her. She survives the realm of the Barrowbane and the River of Lamentation. She makes a reconciliation with Death and comes to the Well at the World’s End. But while she has been on her quest, time has passed, and the Celtic world has faded away.

At the end of the book a young woman from modern Edinburgh meets Meggie by St Margaret’s Loch, under Arthur’s Seat, and the doors to the Otherworld reopen for both of them.

The book itself is more like a vision than a 20th century novel. Plot and character are less important than the vision of the Otherworld and its realisation within ourselves.

The vision is composed with care and in detail. D’Ambrosio even composed music to go with the poems in the book. The story of 175 pages seems to contain a lifetime’s imagination.

There is no hint as to how or why D’Ambrosio came to write the story. She cites only a few sources. She may have explained more when she gave a reading from the book, and some people must still remember it. It’s to be hoped that more about her life and her other writing will emerge. The novel seems to address the pain of bereavement, and as she reaches the World’s End, Meggie says, ‘Between death and love, life dances forever.’ The work she might have done if she had lived is lost, but we still have her novel and perhaps, a quest of our own – to speak out together and protect women – and to remember her as a radical dreamer, part of Edinburgh’s creative history.

Published: 22 March 2021

Leave a Reply