Category: Uncategorized

-

Our Top Queer Books for Halloween

As the nights are drawing in, it’s the perfect time to curl up with a creepy, spooky or unsettling read. And there’s no end of queer horror books to choose […]

-

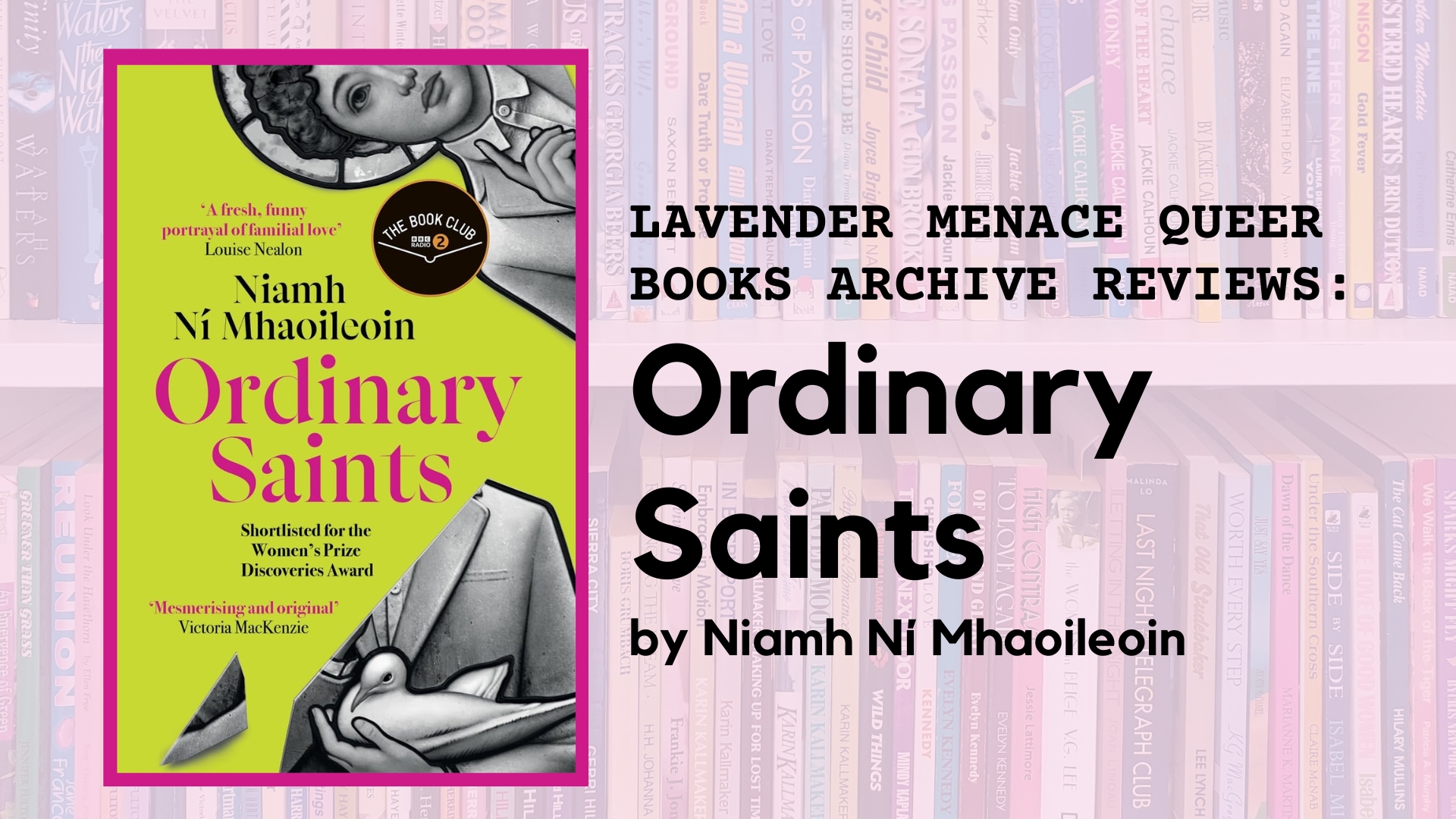

Book review: Ordinary Saints by Niamh Ní Mhaoileoin

Lavender Menace volunteer Katie Marson interviews Ordinary Saints author Niamh Ní Mhaoileoin. Thanks to Bonnier Books UK for the review copy and arranging the interview! Overview Niamh Ni Mhaoileoin’s Ordinary Saints is […]

-

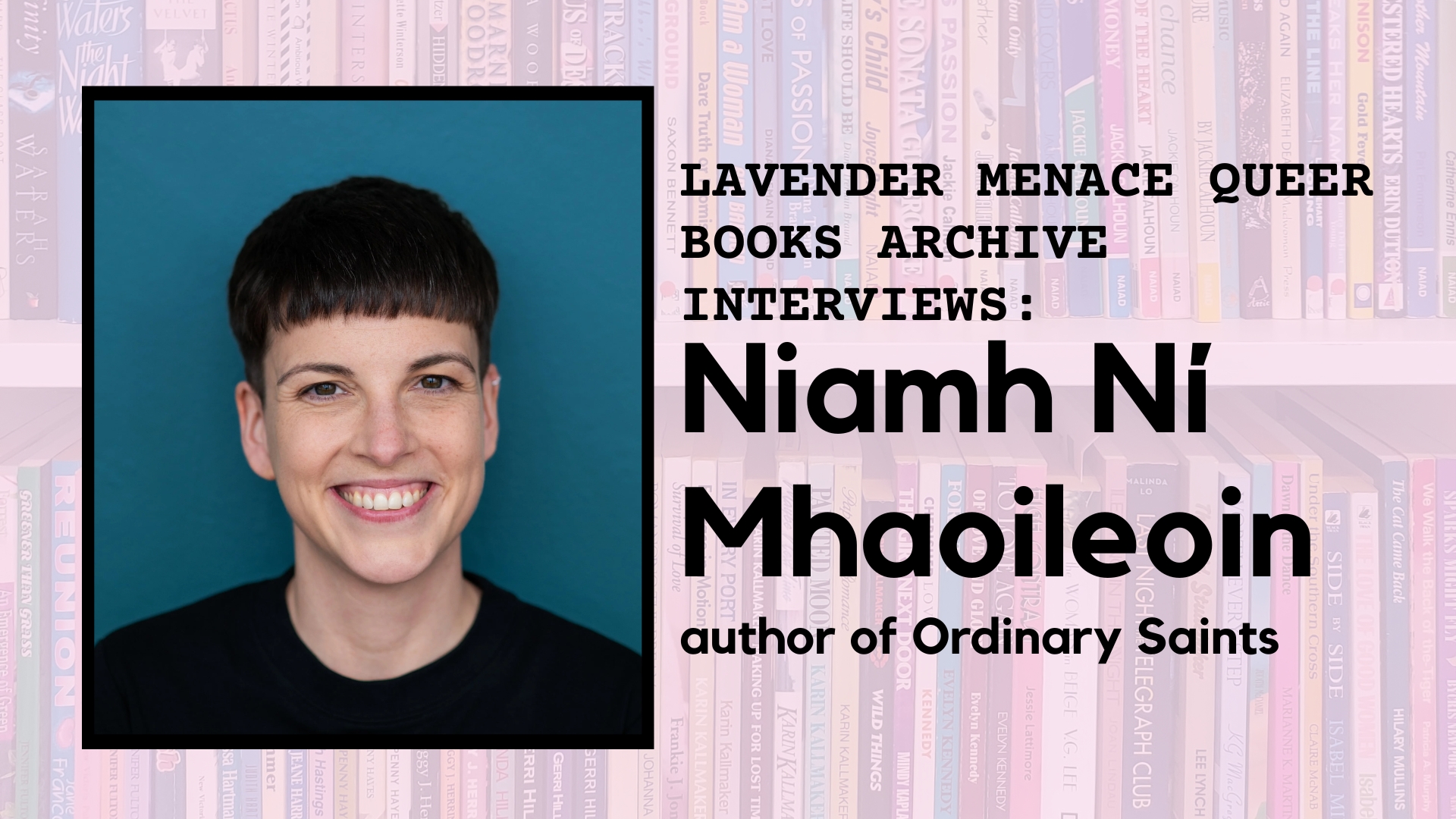

Interview with Niamh Ní Mhaoileoin

Lavender Menace volunteer Katie Marson interviews Ordinary Saints author Niamh Ní Mhaoileoin. Thanks to Bonnier Books UK for the review copy and arranging the interview! Transcriber’s note: this interview was […]

-

Elizabeth Calvert: 17th-Century Radical Bookseller

What can 17th-Century Radical Bookseller Elizabeth Calvert Teach Us in a Modern Age of Book Bans? by Ali Leetham The US Education Department decided to end its investigations into book […]

-

Book review: Marsha by Tourmaline

Lavender Menace volunteer Cooper King reviews Marsha: The Joy and Defiance of Marsha P. Johnson by Tourmaline. Thanks to HarperCollins for providing review copies for this blog and for our […]