Peter Parker is an acclaimed author of biographies and histories, with a particular focus on twentieth century queer writers such as Christopher Isherwood and J R Ackerley. His latest book is Some Men in London, a two-volume anthology of writing about gay life in the English capital between the end of World War Two and the partial decriminalisation of homosexuality in 1967.

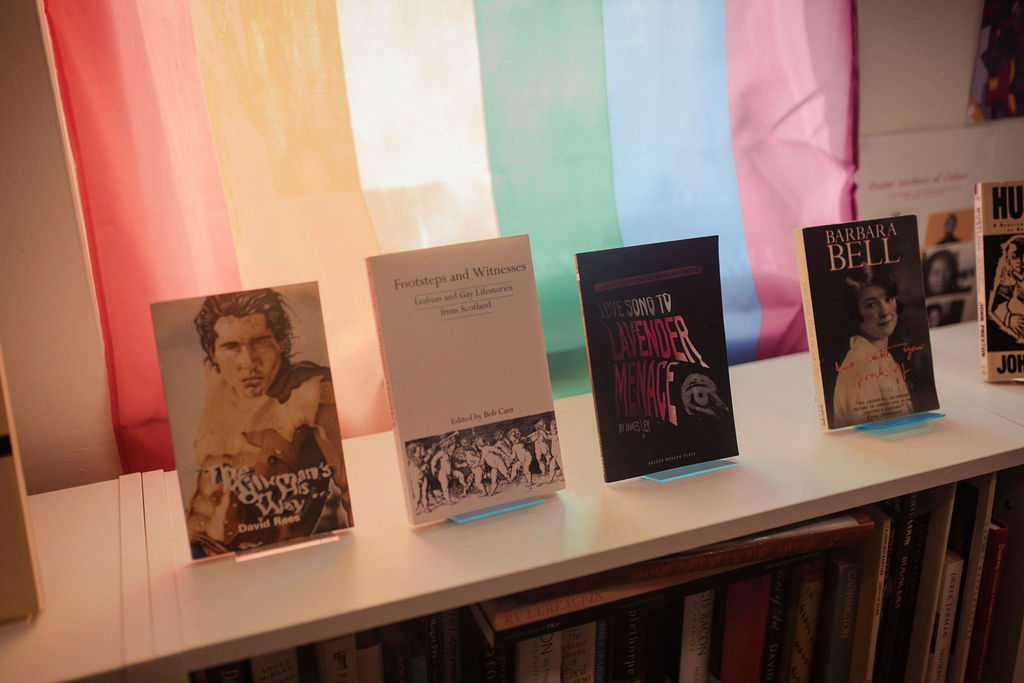

In June, Peter was in Edinburgh to promote the book and kindly agreed to drop in to the Lavender Menace Queer Books Archive to chat about queer lives and literature and many other topics close to the hearts of the Lavender Menace team.

In this first blog piece, Peter discusses police raids, moral panics and the power of queer literature

The interview has been edited for length and clarity. Trigger warnings: homophobia, mental health, suicide.

Lavender Menace: Peter, welcome to Lavender Menace.

Peter Parker: Thank you very much. It’s very nice to be here!

LM: How well do you know Edinburgh?

PP: Well, I thought I knew the city better than I did, but I haven’t been here since 2018 and it’s amazing how different it looks. It’s probably me that’s different rather than Edinburgh! I think if I was here for longer, it would all start coming back.

LM: Do you have any memories of West and Wilde or Lavender Menace, the book shops?

PP: No, I think I was always coming up here for such a short time and very much as a tourist with friends who were showing me the sights, very much the typical tourist sites, and some less typical. I just spent the morning in the National Gallery [of Scotland], and I’d forgotten what an extraordinary collection it is. I mean it is staggering. It’s absolutely on a level or even—perhaps I shouldn’t say—better than London’s National Gallery. It really is fantastic. Almost every picture you see, you think, ‘My goodness, that’s good!’ or, ‘Oh! I know that picture. I had no idea this is where it was.’

LM: On your Instagram account (@prnparker), you do post about art as well as literature…

PP: Yes, I write about art as well for Apollo magazine. So that’s another string to my bow.

LM: We might come back to some of those other strings a bit later, but I wanted to dive straight in with your latest book Some Men In London. Here at Lavender Menace, we’ve just been commemorating the police Operation Tiger in 1984. Not long after the Lavender Menace bookshop opened there was this moral panic and Gay’s The Word bookshop in London, and also Lavender Menace up here, had stock confiscated by the police. There was this idea that it was material likely to ‘corrupt’ impressionable minds. And it’s another moral panic in 1945 where you start your book, Some Men In London. So, I wanted to ask you a bit about this idea of moral panics—they keep coming back.

PP: I’m afraid they do. One would hope we were beyond them now. Other people have talked about Clause 28 [Section 2A in Scotland, which prohibited the ‘promotion of homosexuality’ by local authorities. It was brought in by the Conservative Westminster government in 1988 and repealed in Scotland by the Scottish Parliament in 2000]. And it’s that thing: you think we’re making progress and suddenly it’s as though you’re slapped back again. I’m a sort of child of the gay liberation movement, which is one of the reasons I’m not doing a third volume of Some Men In London. People always ask, and I’ve said, well, for me that isn’t history. You know, I remember too much about it! In fact, it’s interesting you should mention those raids and the confiscation at Gay’s The Word. I was one of the writers they asked to write a defence, and I had to defend Teleny, which, as you probably know, is a near-, well, is a pornographic novel supposedly partly written by Oscar Wilde, and it was quite hard to justify that, but I managed it somehow! I mean, I don’t really believe people are corrupted by books, certainly not books about sex, so I was very pleased to do that. And of course, it’s been the anniversary, so there’s been a lot about that around.

LM: Yes, I think that that’s quite an interesting point that comes up again and again in your book, this idea of the corruption of youth, or the corruption of working-class men who were not supposed to be intrinsically prone to these terrible ‘predilections’ but were corrupted by the idle rich.

PP: Well, I think it’s partly because people didn’t really understand homosexuality. I mean, you could say we still don’t in all sorts of ways, but there was this idea that homosexuality was catching, and this idea of corruption, and it even extended to the theatre. I mean, the Lord Chamberlain’s office, which was the official censor. So, every play that was put on in public, rather than in a club performance, had to go up to the Lord Chamberlain’s office. It’s a very odd thing, to be part of the Queen’s household, to be in charge of censorship of the theatre, and they were all ex-army, all with strings of initials after their names, and they didn’t want homosexuality on the stage at all, though there was a loosening up of that a bit later. But there was this idea that that if young, impressionable men saw any depiction of homosexuality on stage, you know, they’d be corrupted by it. To which the answer is, if homosexuality is that powerful and that attractive, why are you so against it? They also thought that, if there was a play with homosexual characters, all the homosexuals in London would flock to it, and then they’d be wolf whistling each other and misbehaving in the auditorium, which is not what censorship ought to be about. I mean, I don’t really believe in that sort of censorship anyway, but it’s a very different thing saying, ‘This play shouldn’t be put on’, to saying, ‘If we do put it on people in the audience are going to have too much of a good time’!

LM: Yes—there’s a great quote in your book. I think it was somebody that the Lord Chamberlain had asked for advice, who said that ‘The introduction in plays of these new vices might start an unfortunate train of thought in the previously innocent’, which I think any gay, lesbian, or queer person would find an odd statement, you know, that it had never occurred to them until they saw it on stage.

PP: Yes. Exactly. But I know lots of people, and I’d include myself, who sort of found out about themselves in the broader sense by reading books. You know, when I was a teenager, I was rushing through the works of people like Christopher Isherwood and then a very kind schoolmaster introduced me to J R Ackley, which led to me actually writing biographies of these two writers. But various friends like Alison Hennegan, who was the literary editor of the old Gay News when it was a newspaper, and who I worked for, she always said that, oddly enough, she often looked for gay men as a sort of model to be a gay woman, which is an interesting slant. I don’t actually like the idea that ‘gay’ books are only for gay people or ‘Black’ books are only for Black people. I think books are for everybody, but it is true that if you’re young and growing up and aware that you are different, in whatever way, to actually find books about people who also are—I think that’s one of the values of literature.

LM: It’s interesting that you say that because I think that’s a big part of the ethos of Lavender Menace. This idea that, certainly before the Internet, books were the space where gay people could find out about themselves and explore what the possibilities were. The Internet obviously provides huge opportunities for people to engage and to meet people. But whether it does that in the same way that books do—or did? I’m not sure.

PP: I’m not sure. I think that’s because the whole thing about social media and the Internet is you are interacting with people, unless you’re just looking something up on Wikipedia. But when it’s you and a book, there’s no one around shouting at you and saying, ‘This is wrong! This is right!’ It’s you, concentrating on a book.

I have to say that one of the books I did discover, I suppose I was about fifteen or sixteen, was Yukio Mishima’s Confessions of a Mask, which I can’t say is a model for the homosexual lifestyle. It’s mainly about wanting to dress up as Saint Sebastian and undergo sadomasochism. So, you know, I thought, ‘Oh! This is the future? Oh dear!’ It was rather more reassuring to read Isherwood.

LM: We were just talking about Mishima here at Lavender Menace, and how we catalogued his books in the archive. Because he’s not exactly, as you say, a role model necessarily but, yes, an interesting person and obviously he should be represented here.

PP: He’s a very interesting writer, yes.

LM: I wanted to come back to this idea of the moral panic and the fear of corruption, because there is also this other strand that comes out in a lot of the quotes that you have in the book where people are saying, ‘Well, do you know what, it doesn’t really matter if this is on the stage and in books because it’s going to be over the heads of most people, they won’t get it, they won’t understand’.

PP: Yes, but I think there was a lot of intellectual snobbery. I mean, when I say reading ‘literature’, I’m using it in the fairly broad sense. I mean, a lot of what I read as a teenager was not terribly well written. Do you remember Kyle Onstott and Lance Horner? A couple of Americans who wrote the most lurid novels. There was one about the emperor Heliogabalus. This wasn’t the entirety of my reading. It was a great deal of people being tied up with leather thongs, but at the same time this was a world that I sort of understood and felt a certain kinship with—not that I ever wanted to be a Roman emperor, or indeed one of his catamites!

But I think that one wants to be quite careful about talking about literature. It’s like me defending Teleny, which I wouldn’t do as a work of literature, but as a work of history and as a work about the history of sexuality. I mean, it’s like that novel, Sins of the Cities of the Plain, which is anonymous and is a work of pornography, basically. But the details tell you a lot about what the gay world was in the late Victorian period.

LM: Yes, I think that’s a very interesting point. I was talking to my mum about her memories of the sixties and the comedy show Around the Horne on the radio, which she used to listen to as a teenager with her parents who were quite, you know, straight-laced, certainly no discussion of sex at all, never mind homosexuality. And they would have, you know, these gales of laughter, tittering—I think they understood it as vaguely smutty. I listened to it in my twenties and was aghast at how explicit the humour was if you understand the coding, so clearly some of it did go over people’s heads.

PP: I think it did. I mean, there’s one of the sketches with Julian and Sandy, or part of it, that does come into Volume 2—you couldn’t really do it without Julian and Sandy—and it’s interesting that both the actors were themselves gay. They managed to get away with so much, but some of it really was over the heads [of many people]. In fact, the extract I use is one when they’re going to put on a musical and Julian says, ‘Oh! Let Sandy play you some music. He’s a dab hand at the cottage upright!’, which could be perfectly straight-faced: a cottage upright is a type of piano. But we all know what a ‘cottage’ means, and an ‘upright’. And we also know what ‘a dab hand’ means. Or, rather, we do. I think that’s one of their most brilliant lines, and there’s quite a lot! There’s one about camping, which has got some very good lines and there’s one about something to do with criminality and briefs and, you know, it’s all this double entendre.

LM: Yes! ‘Legend has it many queens have slept in this bed. But not all at once!’

PP: Yes, but compared to, say, the Carry On films which Kenneth Williams always did, which were full of innuendo, they were very sophisticated, and actually written by these straight men, as it happened, Barry Took and Marty Feldman. But it’s quite clear that there was a great deal of improvisation going on—and a lot of corpsing. It’s rather wonderful, and you suddenly hear them having to say, ‘Ooh go on! Go on, Mr ’orne!’ when he’s obviously corpsing terribly, and that’s part of its charm, obviously.

LM: Something that comes up a lot in the gay men’s literature group that we run here at Lavender Menace, is all of these twentieth century literary circles, where there were a lot of queer people. John Lehman is maybe the obvious one but, thinking about the Bloomsbury Set and this period of the twentieth century that you specialise in, there do seem to be a lot of groups of literary, artistic people where sexuality was much freer and they were able to express themselves. And I think there’s something very attractive about that: we look back on this and we think, ‘What a marvellous time they had!’ And yet a lot of them came from very privileged backgrounds and so they were able to carve out these bubbles, where they could be themselves, when perhaps other people didn’t have that opportunity. But, as you highlight in Some Men in London, lots of people who were not privileged were also managing to have quite a lot of fun as queer people outside of those ‘walled gardens’.

PP: Yes, I think that’s true. It’s one of the things I did want to emphasise in the book, because there was far too much written at the time about how working-class people couldn’t possibly be gay unless they were corrupted—and it just isn’t true. When you look at court records, you can see it isn’t true. But it was a myth that was peddled, you know, right on through the discussion of the Wolfenden Report.

It’s more difficult to represent this because obviously the educated, privileged people, if they were writers, they were writing novels or poems or autobiographies or memoirs, and it’s the people who weren’t writers, who had equally interesting lives, but they’re less recorded. But that doesn’t mean that that they shouldn’t be represented. There are ways to find stuff and a lot of it is to do with court records and following through and finding newspaper stories.

There is—and always has been—a large working-class population of London. I live in the East End, and I was fascinated to find stuff about the East End. You think of gay clubs, gay pubs, and they’re all in Soho, Fitzrovia, in the West End. But of course, there was an equally thriving culture [in the East End]. And then you had the Krays going between the two. I mean, the Krays are not exactly role models for any kind of behaviour, but fascinating in themselves, particularly with their fingers in every pie. I mean, talk about corruption—that really was corruption. They would run a club and find the prettiest boys they could to serve the wine and be croupiers, and then get all these politicians and people in high places in. And then set them up and extort, not usually money, but favours. You find people like Lord Boothby and Tom Driberg behaving so recklessly, being provided with boys by the Krays and then—it does seem unbelievable— you find them in Parliament when the Krays were in prison sort of saying, ‘Oh, the Krays. Of course they’re very wicked, but I think perhaps they’re being treated a bit harshly.’ Well, you know, they can’t really have believed that. And one assumes that some sort of pressure was being exerted on them, in order to say that.

LM: I think that’s one of the interesting things that does come over in the book: the intersection between all of these layers of society. That, somehow, the queerness to an extent broke down some of those social barriers and allowed people to move up and down.

PP: Well, my very first book was about the First World War and the public school system, The Old Lie, and it was certainly true that a lot of the officer class had never actually met [working-class men]. I mean, they may have had a servant, someone to drive their car or clean their boots. But in the extreme circumstances of the trenches, when they were all in it together, they suddenly realised that these were real people, not put on earth just to serve them.

There were lots of officers who retained that sort of sense, but of course the gay ones, say, people like [Siegfreid] Sassoon and [Wilfred] Owen, found themselves drawn to these lads, as they always call them, taking the Housman model. And it did break down barriers to some extent. And then the Second World War, I think, did it even more because by that point the servant class had more or less been wiped out, either in the trenches or through death duties—people couldn’t afford them, and the middle classes had to fend for themselves. So, by the time you got to the Second World War class barriers were again broken down, and I think sexual barriers as well. I mean, one of the reasons there was a moral panic was it was thought that homosexuality was on the rise. And one of the reasons it seemed to be on the rise, or one of the causes, was having fathers away at the war and not exerting paternal pressure, keeping their sons in check and showing them the right masculine way to be. I mean, I don’t think there’s any evidence that there’s actually a link at all, but this is what was thought.

There seemed to be a rise in prostitution because obviously prostitution had thrived in the war. Men away from their wives, if they were married. Women away from their husbands, perhaps having extramarital relations. The divorce rates went up. So, there was this idea that all these things were coming together to create this: the end of civilization as we know it.

But the obverse of that is that there have always been middle-class gay men who fancy ‘a bit of rough’. And that is just one of those psychological things that is difficult to explain, but I think it is to do with difference. Isherwood always said he would never be comfortable having a sexual relationship with anyone of his own class. I mean, it didn’t stop him having a long affair, on and off, with Auden, but that was his view. Ackerley was much the same: it was waiters, it was guardsmen, it was deserters—until the dog came along! And John Lehman, who you mentioned just now, you know, there was this attraction to ‘he ‘other’. And, also, there is that sort of attraction to danger that certain gay men certainly used to have. I don’t mean they wanted to be beaten up or anything but somehow there’s a frisson, you know, you’re crossing a class barrier. I mean, E M Forster is absolutely brilliant talking about that frisson, this idea that—he doesn’t put it as bluntly as this—but through homosexual relationships, you can leap class barriers, you can leap race barriers and show that they’re meaningless. Forster is my hero. I’m lucky enough that I was given by May Buckingham, the widow of Forster’s policeman, a photograph of Forster taken by George Platt Lynes, which hangs behind me as I write. An American friend some years ago came and said, ‘That’s Sir George Platt Lynes—an original print! Have you any idea how much it’s worth?’ I said no, and please don’t tell me—I just don’t want to know!

Like a lot of people, when I first thought about Forster I thought, you know, unlike Isherwood or Ackerley, he was this sort of fussy old aunty. And because he wouldn’t publish [his gay novel] Maurice during his lifetime, a later generation of gay men have criticised him and said, ‘What a coward!’ and ‘He’s a disgrace!’ One of the things I was determined to get into Some Men in London is to show how much he was doing, like writing letters to the newspapers. He was writing articles. He was donating very large sums of money to the Homosexual Law Reform Society. And what I didn’t know is that the famous letter that A E Dyson, the academic, drafted to urge the government to act on the Wolfenden Report—it was a letter to The Times signed by the great and the good, all these philosophers and bishops—and Forster actually helped to draft that anonymously. I’m always really pleased when I find out a bit of gay history that I don’t know. And if I don’t know it, I’m hoping that the readers won’t!

LM: We were talking about how many of the people in these literary and artistic circles lived in a sort of gilded, protected world, but actually there were limits, weren’t there? Even someone like [Conservative MP] Chips Channon, you know, if he went too far…

PP: Yes, he was worried that his relationship with [dramatist] Terence Rattigan was becoming the talk of the town. I don’t think he had a great deal to worry about, but there is the case of [composer, Benjamin] Britten and [society photographer] Cecil Beaton, who were called in by the police. Nothing happened, but it would have been very frightening.

LM: So, they were living in fear like everybody else.

PP: Yes, I think within their own circles they were perfectly open about it. I mean, everybody was always criticising Stephen Spender but World Within World was a very brave book to publish. I don’t use it because he’s mainly writing about the 1930s but, without him actually saying, it’s quite clear from the context that his relationship with his secretary, Tony Hyndman, this was a proper relationship, and to write that in 1951 was, I think, fairly courageous.

—

Some Men in London by Peter Parker is available to buy now! We encourage you to shop from your local independent bookshop. Keep an eye out for our next blog with the rest of this interview with Peter Parker coming soon!