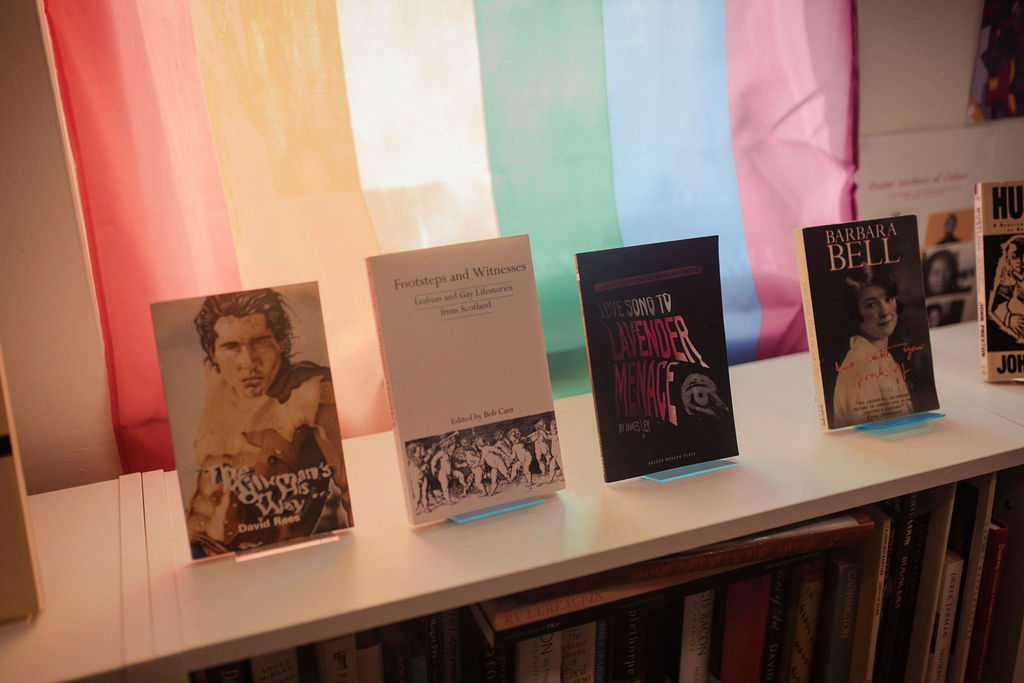

Category: Queer Archive

-

Archiving Queer Futures: Eman Abdelhadi in conversation with Nat Raha

You can now watch the recording of this event online. Lavender Menace hosted an online discussion between two activist scholars on imagining and archiving queer futures. Dr Eman Abdelhadi is […]

-

Dorian the Maenad

Lavender Menace volunteer, Michael, explores the queer links between The Picture of Dorian Gray and the Cult of Dionysus.

-

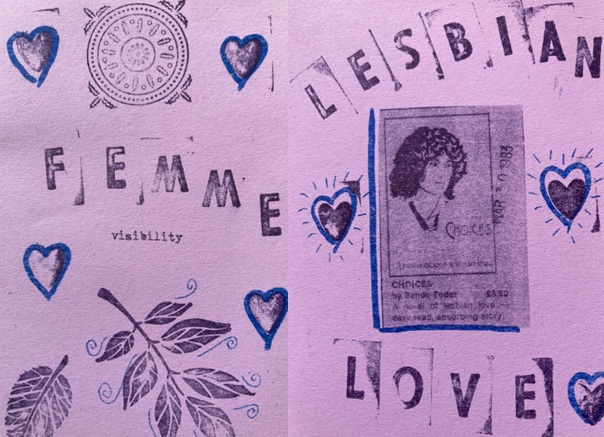

Lavender and Menaces

The clothed lesbian body as a tool of resistance, the sapphic significance of purple, and the making of the modern-day femme

-

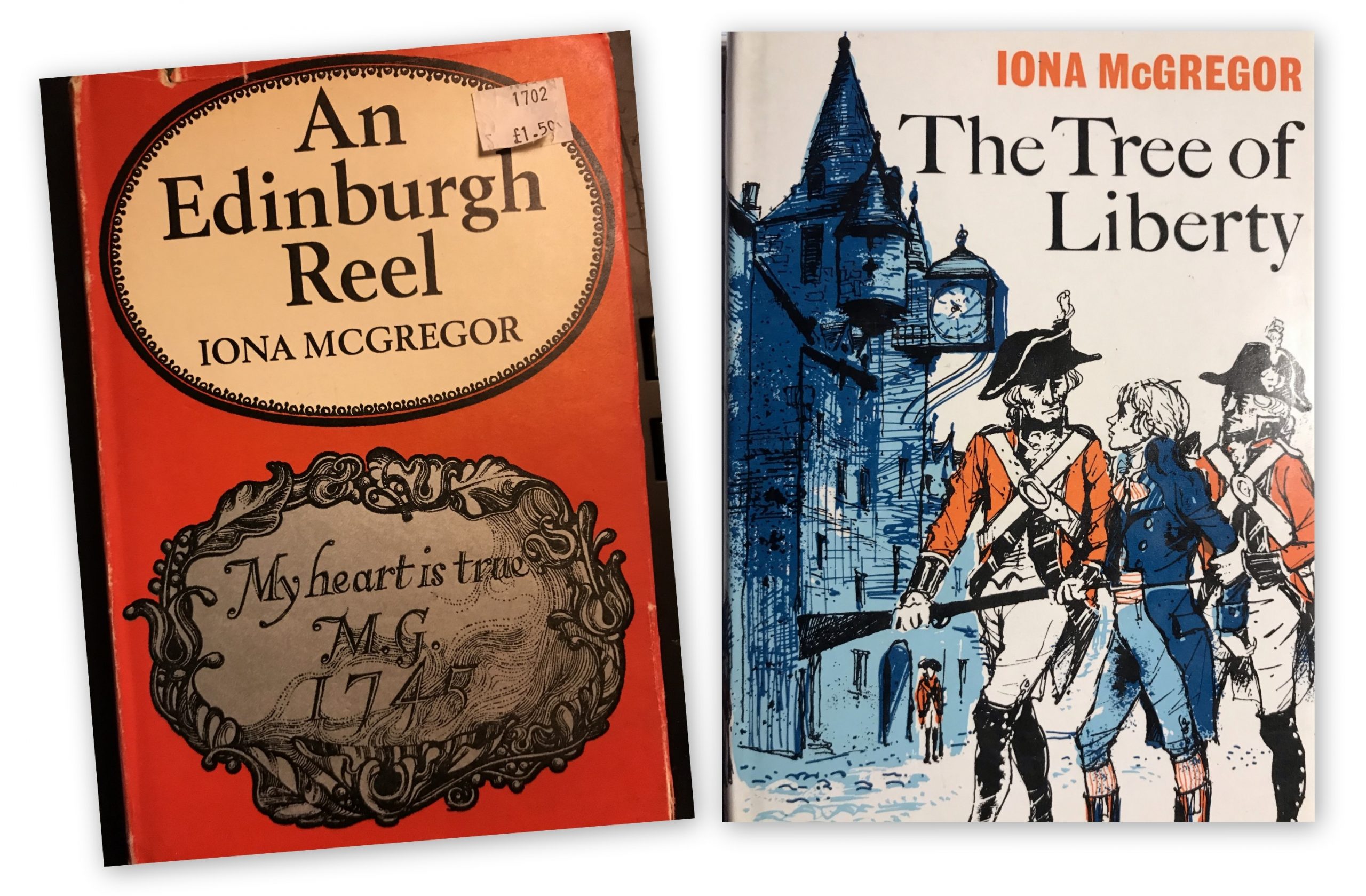

A Lavender Attic

‘LGBT+ archives,’ says Gerard Koskovich of the GLBT Historical Society of San Francisco, ‘are your queer grandma’s attic’. They are the place where younger generations will find our legacy.