The clothed lesbian body as a tool of resistance, the sapphic significance of purple, and the making of the modern-day femme

To celebrate lesbian visibility week this year, I decided to explore the origins of the phrase ‘Lavender Menace’, originally a derogatory term used against lesbians during the feminist movement and reclaimed by a group of radical lesbian feminists in the 1970s. I am particularly interested in the use of the colour purple and flower imagery like lavender and violets as signifiers of queer, but more specifically sapphic, identities. I am also interested in how these symbols function to inform, or are reflected in, modern-day lesbian fashion trends, particularly that of the ‘femme’ lesbian, whose visibility in the queer community is often less visible. I was recently lucky enough to access Eleanor Medhurst’s fascinating lecture from the Feminist Lecture Programme ‘Dressing Dykes: A History of Lesbian Fashion’ promoting her new book, Unsuitable: A History of Lesbian Fashion, which further inspired my interest in this topic. I have always been interested in the use of clothing as a tool of resistance, and the Lavender Menace’s origin story is a particularly impressive example.

Who were the ‘Lavender Menace’?

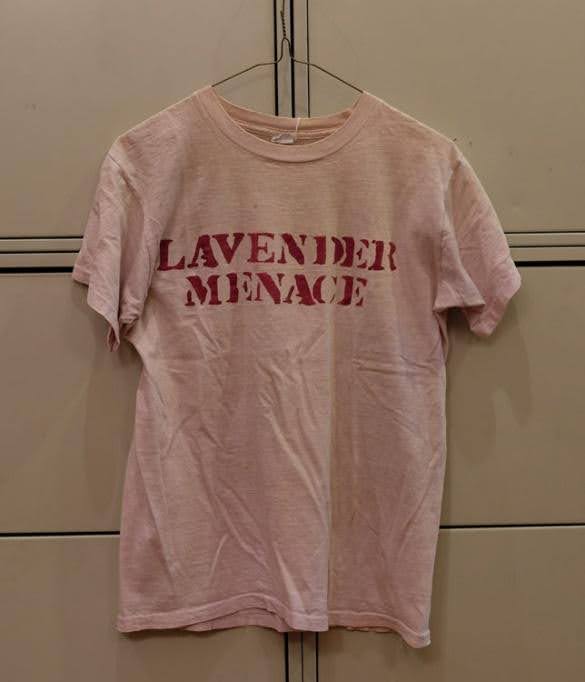

The Lavender Menace were a group of radical lesbians who were particularly active in the 1970s. For them, this meant women who only put energy into engaging with other women in their political and romantic lives. The phrase ‘Lavender Menace’ was reportedly first used by Betty Friedan, president of the National Organisation for Women (NOW), to describe the threat that she believed lesbians posed to the feminist movement. This statement led to the exclusion of lesbians from the Second Congress to Unite women which took place in Maine in 1970. Lavender Menace, alongside women from the Gay Liberation Front, were not willing to let this happen and planned an act of direct lesbian action through which they were going to infiltrate the conference to make sure their voices were heard. This is where lesbian fashion history becomes so important, as the Lavender Menace T-shirts the women wore formed the basis of their protest. On 1st May 1970, the group of women turned up to the conference wearing different shirts over their hand-dyed T-shirts with ‘Lavender Menace’ printed across them so they could blend into the crowd. Once the conference had begun, the Menaces arranged for the lights to be switched off for a short period, during which time they quickly removed their cover-up shirts and seventeen lesbians stood up in rows on the aisles of the hall so that the Lavender Menace T-shirts were on full display. When the lights came on, one of the Menaces, Karla Jay, stood up from where she’d been sitting undercover in the audience. She describes how she unbuttoned her long-sleeved red blouse and ripped it off, exposing the T-shirt underneath. Shortly after, another Menace, Rita Mae Brown shouted to members of the audience, “Who wants to join us?”, to which around twenty hidden Menaces in the audience replied, “I do, I do.” They also held up signs which read, “The women’s movement is a lesbian plot” in an ironic reclaiming of the narrative that had been used against them.

“Lesbian bodies and the garments that clothed them were the basis of the Lavender Menace’s activism.”

Eleanor Medhurst

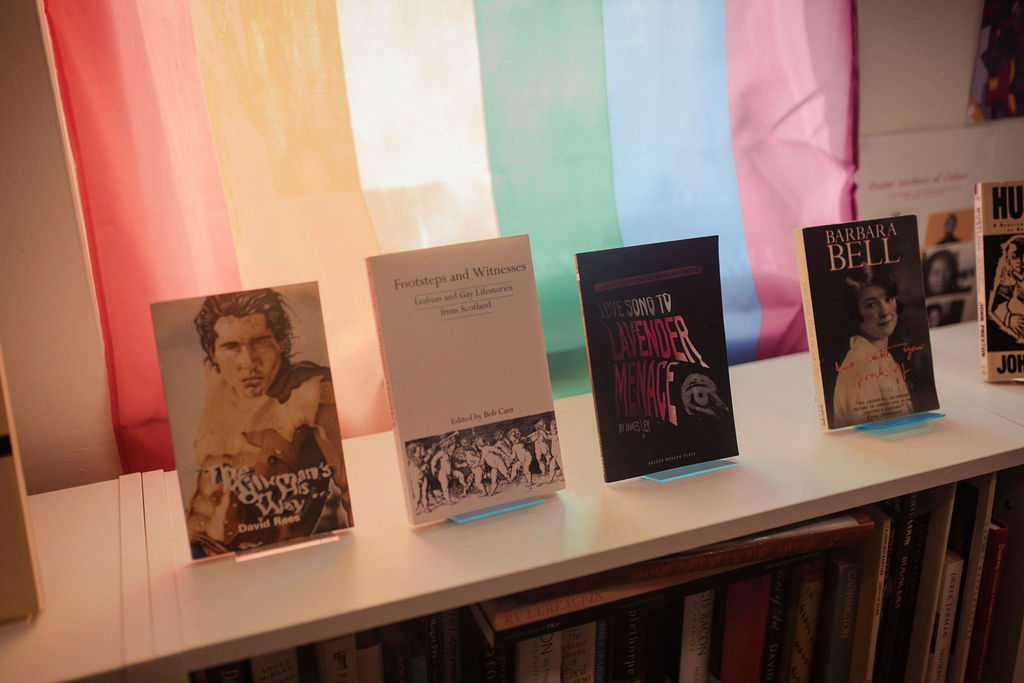

The effects of this infiltration were important, since this protest had forced lesbian issues out in the open. During the rest of the conference, other lesbians took to the stage to voice their pride. The result of this direct action was that NOW passed a resolution acknowledging the double oppression of lesbians as women and homosexuals and recognized the “oppression of lesbians as a legitimate concern of feminism” in 1971. The promise that “Lavender Menace will strike again–anywhere, anytime, anyplace” had obviously been somewhat effective. Effective enough, in fact, to reach the UK, inspiring the name for the first queer bookshop in Scotland in 1982, and of course today it is the name of the queer events space and archive I volunteer with.

Medhurst also explores the significance of the Menace’s hand-making their T-shirts, since this represented the time, energy, and labour they were willing to put into their lesbian activism. The T-shirts were hand-dyed in a bathtub and then silk-screened with the phrase ‘LAVENDER MENACE’. Notably, no two shirts looked exactly the same despite the fact they all had to be the same size due to funding restrictions. Medhurst writes that ‘by creating or customizing a garment by hand, a more powerful, specific, and decisive story can be told’, which is exactly what the Menaces achieved with their hand-dyed T-shirts.

Why ‘Lavender’?: The sapphic significance of purple

Medurst referenced her research into the queer significance of the colour pink during her lecture, drawing on examples such as the pink pound and the pink triangle. Pink, she explains, is a big part of queer visual culture. For queer women in particular who rebelled against the colour because they felt that pink was imposed on them from a young age, the reclamation of pink feels particularly powerful. But what is it about the colour purple that also gives it such strong queer associations?

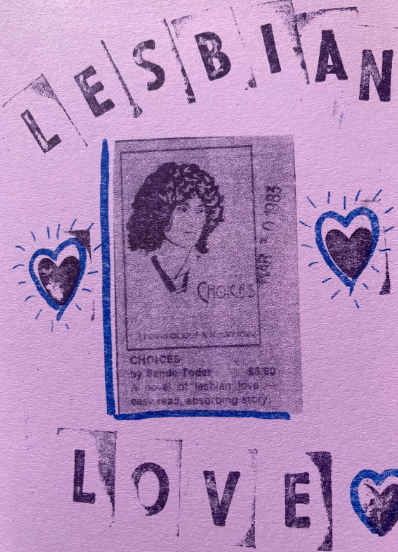

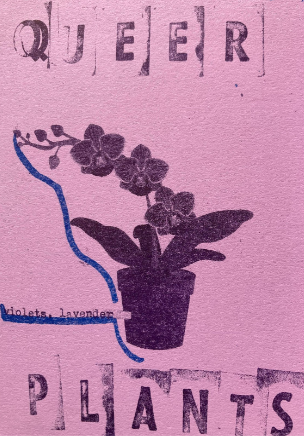

By 1970, Medhurst notes, lavender had already been ‘cemented as a shorthand for gay, queer, or different’. Vibrant purple shades were difficult to recreate outside of nature, meaning they were reserved for the rich until the nineteenth century. This resulted in the colour adopting an air of mystery and glamour which it retained even when it became a more accessible colour. Sappho wrote of girls adorned in flowers, wreaths of violets worn as a crown or woven around their “slender necks” in her poetry, as well as referencing purple hyacinths and crocuses to symbolise love between women. The violets are often used to adorn the women Sappho describes, showing how clothing the queer female body with purple functions as an act of resistance. The queer symbol continues to emerge in literature and film; for example, Tennessee Williams’s Mrs. Violet Venable in Suddenly Last Summer, the fields in Alice Walker’s The Colour Purple, and Violet in the lesbian cult classic film Bound. Of all the shades of purple, Medhurst writes, ‘lavender is that which is most associated with lesbians and the LGBTQ community’, re-emerging in the 1990’s with the ‘Lesbian Avengers’ who handed out lavender balloons during a school protest. The women also wore T-shirts that read “I was a lesbian child” and encouraged children and parents to “ask about lesbian lives”, again demonstrating the power of the clothed lesbian body as a site of activism.

Beyond its sapphic connotations, the term also has its roots in the stigmatisation of homosexual men. It is interesting and quite amusing that lavender is used in this way, as the flower is more fragrant, delicate, and sweet, than it is threatening. I think this is what makes the reclamation of the symbol so compelling, and it is something I feel particularly drawn to today as a femme-identifying lesbian with a love of purple and anything floral.

The modern-day ‘femme’: hyper femininity and purple flower imagery

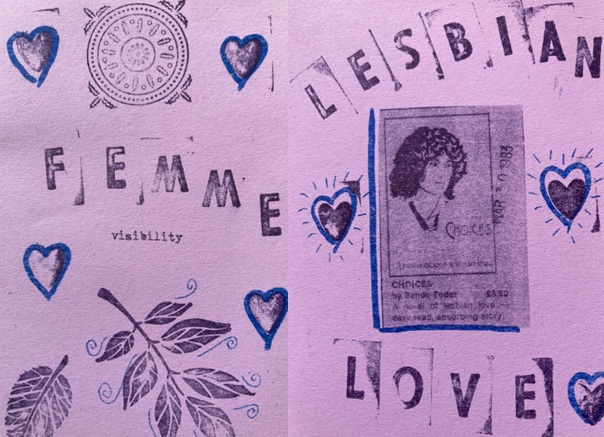

For Lesbian Visibility Week this year, I decided to climb up Calton Hill dressed (almost) head-to-toe in the iconic lavender shade, including lavender earrings and bright purple makeup. Today, there are ‘Lavender Menace’ T shirts and pin badges, as well as violet brooches, hair clips, and earrings, like the hand-painted lavender ones I wore up Calton Hill. This reflects on the power in choosing to adorn ourselves with these visual symbols of our identities as well as Lavender Menace’s powerful legacy, particularly in terms of using clothing as a tool for resistance. Since homosexuality wasn’t decriminalised in Scotland until 1981, and gay men were often the targets of police raids, Calton Hill is known for its historical (and present day) role as a cruising spot at night for gay men. I thought its rich queer history made this the perfect place to take pictures. I wanted to celebrate the hyper-femme style that sometimes goes under the radar when it comes to celebrating lesbian fashion and prove that femme lesbians are not only real but that we can also climb up Calton Hill in massive lavender-coloured heels.

In the present day, butch and femme identities are much more fluid than they once were in the sapphic community. This means some queer women choose to identify in this way, which can be very empowering, whereas others choose to reject these identities completely. The cultural shift away from stricter butch/femme dynamics is complicated and it is important to note that these roles are not rooted in heterosexist culture in the way that mainstream culture sometimes portrays them. Personally, I find femme to be an empowering identity and often enjoy experimenting with what this means for me. Hyper-femininity is a form of expression for some femme queer women which is powerful because it showcases a type of femininity that men often find unappealing. In short, it is often too much for them to handle because it is beyond the threshold of what they find acceptable expressions of femininity. Of course, any queer woman or person can find power in reclaiming lavender and violet imagery, but I think there is something particularly appealing and powerful about it for femmes. Often, we go completely under the radar unless the person is in the know, which of course can lead to feelings of invisibility, but for me it can also sometimes make me feel like I am undercover. This partly inspired my decision to get a tattoo of lavender and violets a few months ago, something I found empowering and validating because it is subtle enough to signify my identity to other queer people whilst still allowing me to go undetected if I want to. This, I have found, is a fun way of making straight people uncomfortable when you choose the right moment to challenge their assumptions about you.

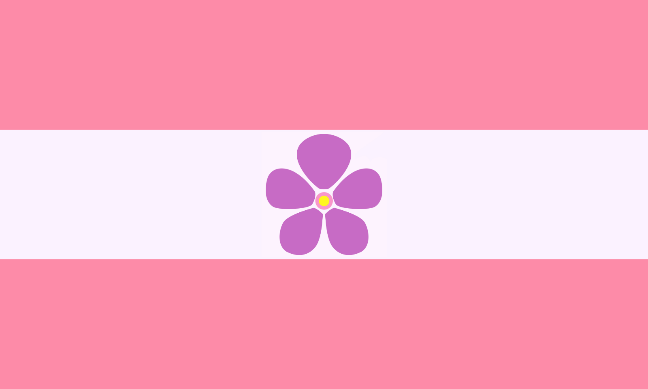

Finally, I want to reflect on the colours and design of the sapphic flag, which has clearly been influenced by Sappho’s purple flower imagery. Medhurst herself argues that ‘flags have become kind of queer communication unlike any other’, and I feel the sapphic flag has an extremely important story to tell. The flag was created in 2015 by a Tumblr user and features both pink and purple, the all-important sapphic colours. It quickly became one of my favourites once I started to research the meaning behind the colours and the violet in the centre.

The second example features two violets, which represents the love between two women. The incorporation of both the pink and purple is something I am, of course, drawn to, and I love how it represents the sapphic community’s long history of resisting homophobia, misogyny, and increasingly transphobia within the sapphic community. It is a symbol of inclusivity, resilience, and pride.

About Georgie (she/her): I’ve been a volunteer with Lavender Menace for a year and enjoy researching and writing about the queer community. I also write blogs for LGBT Health and Well-being, so please have a look if you are interested.