Copyright Lighthouse Bookshop

Evening falls in Edinburgh on 17 November 1860:

In the Royal Mile, former police inspector James McLevy is walking his dog, Jeanie, named for one the city’s notorious thieves.

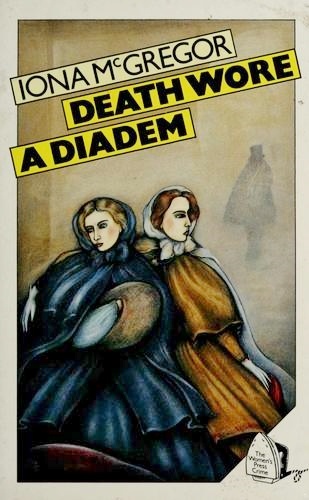

At Waverley Station, the Empress Eugenie of France is arriving. Two demonstrators leap from the crowd, but the Empress and her ladies escape to Douglas Hotel in St Andrew Square. There they unpack a glittering diadem – made, not of diamonds, but of paste. Though the jewels are false, they are about to lead to theft and sudden death.

A short distance away at Moray Place, at the Scottish Institute for the Daughters of Gentlefolk, the scheming headmistress, Lady Superintendent Margaret Napier, is writing up her secret dossier. In the students’ quarters, Christabel MacKenzie, handsome, clever and rebellious, is composing a sonnet about her lover, Eleanor.

This is the opening sequence of Iona McGregor’s historical novel, Death Wore a Diadem, a mystery published by The Women’s Press and launched in 1989 at West & Wilde Bookshop.

For the purposes of the launch, we called it ‘a lesbian mystery’, and Iona herself calls it a lesbian novel in an interview. But even this brief outline shows that it was more besides – a portrait of many characters, from an empress to a detective to a madam, with a lesbian heroine at the centre.

Many lives in one frame

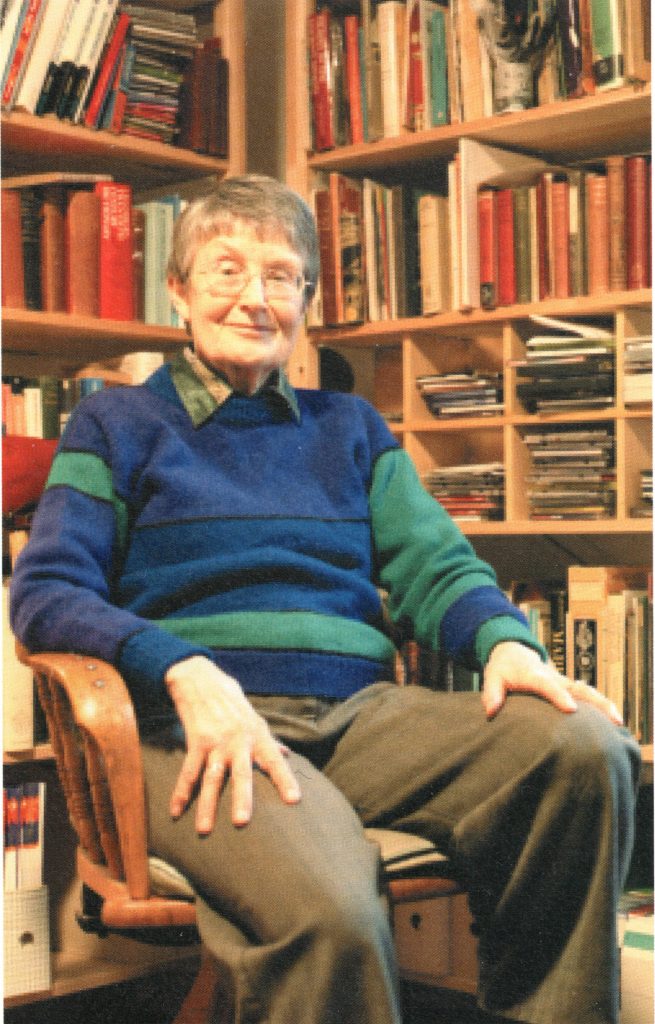

Describing Iona’s career gives a similar impression: many lives in one frame.

She told us the launch of Death Wore A Diadem represented an important moment for her – the first lesbian novel she had been free to write. She was animated as she spoke about her central character, Christabel MacKenzie.

The novel opens on Christabel’s 17th birthday. Like many fairytale heroines she is an orphan. She loves rambling over the countryside, shooting guns, and spending the day in bed with her lover. Left to educate herself in her radical grandfather’s library, she is a free spirit who does not fit well into the life of a Scottish lady. But is confident she can live as she pleases. In the story, despite the machinations of her nemesis, Lady Superintendent Napier – she succeeds.

For Iona, however, life was not often like this. (She certainly did not intend Christabel as a self-portrait, but as a lesbian who could have been, one dealt a run of cards for peril but also for good fortune and courage.)

Early life

Iona was born in 1929 – in England rather than Scotland, but she explained that she would have been born here if she hadn’t been premature. Her father was a teacher in a military school. She had a rough and physically active childhood with his male pupils for friends. She was a Catholic (though as an adult she had no religion) and ‘a great tomboy,’ and prayed to be transformed into a boy every night. (If God could move mountains, why couldn’t he do this?)

Later she said she was not sure whether she had been transgender or simply determined not to accept the feminine role.

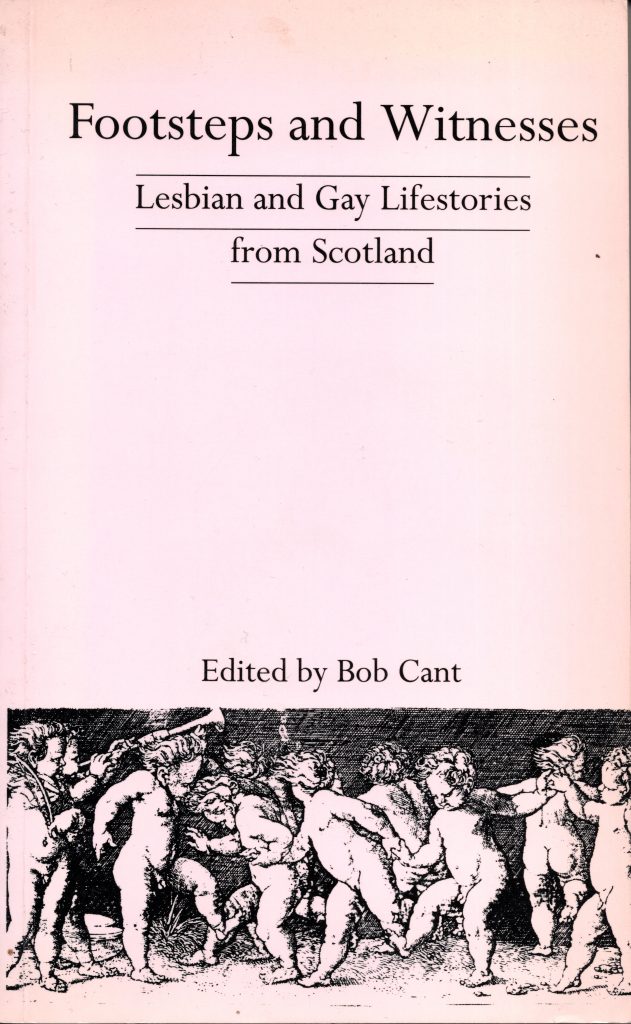

Sent to a convent school, she argued with the nuns about Darwin. Moved to a school in Monmouthshire, she took well to the classics, especially when she discovered ‘Sappho et cetera’. She told Bob Cant, in his book about Scottish queer lives, Footsteps and Witnesses, that she had known from age eight that she was different.

Finding herself

As a young woman she settled in Edinburgh, a city she had always loved. But she found it impossible to meet partners or even lesbian friends, and so she moved to London. She found a job as a grammar school teacher, and quietly explored the fringes of the lesbian scene.

Once, she told the Remember When Project, she met a woman who had been an ex-girlfriend of Prince Ranier of Monaco. They went to the Gateways lesbian pub together and had a brief relationship.

Then she met the woman her friend Marsaili Cameron describes as ‘the love of Iona’s life’. They were together for 12 years and moved to Edinburgh. A few years later her partner left, swayed by family pressure and the sheer pain of a life in which everything had to be kept secret.

Her activist years and early writing

It was then that Iona became what we would now describe as an activist.

Why did she do it? The risk in those days was enormous. She was teaching at an exclusive school. Any exposure of her real life would have ended her career. But she may have decided she had had enough of secrecy.

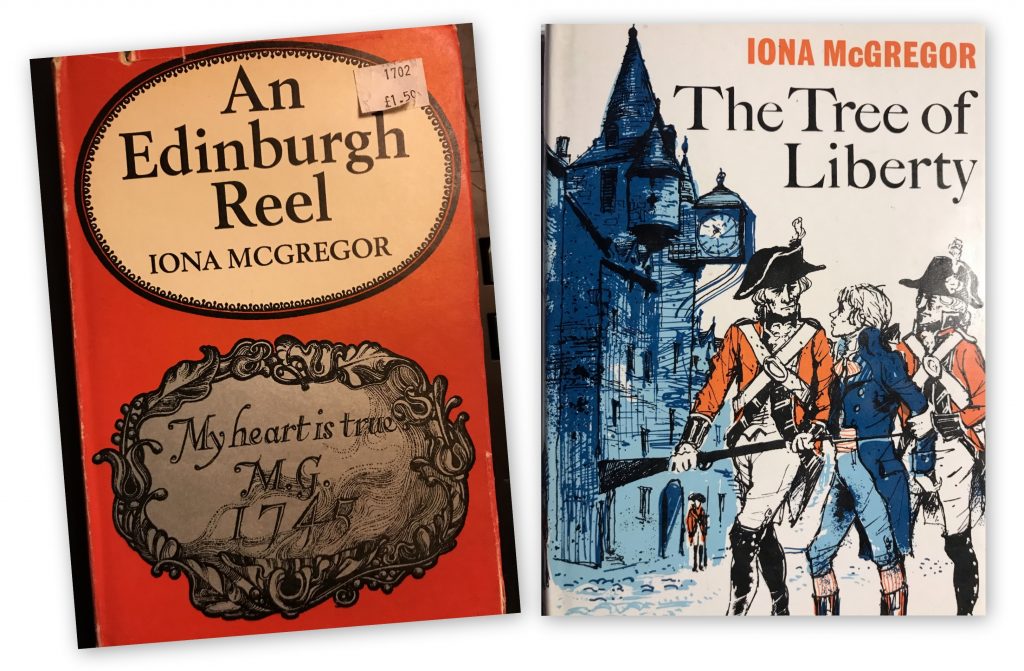

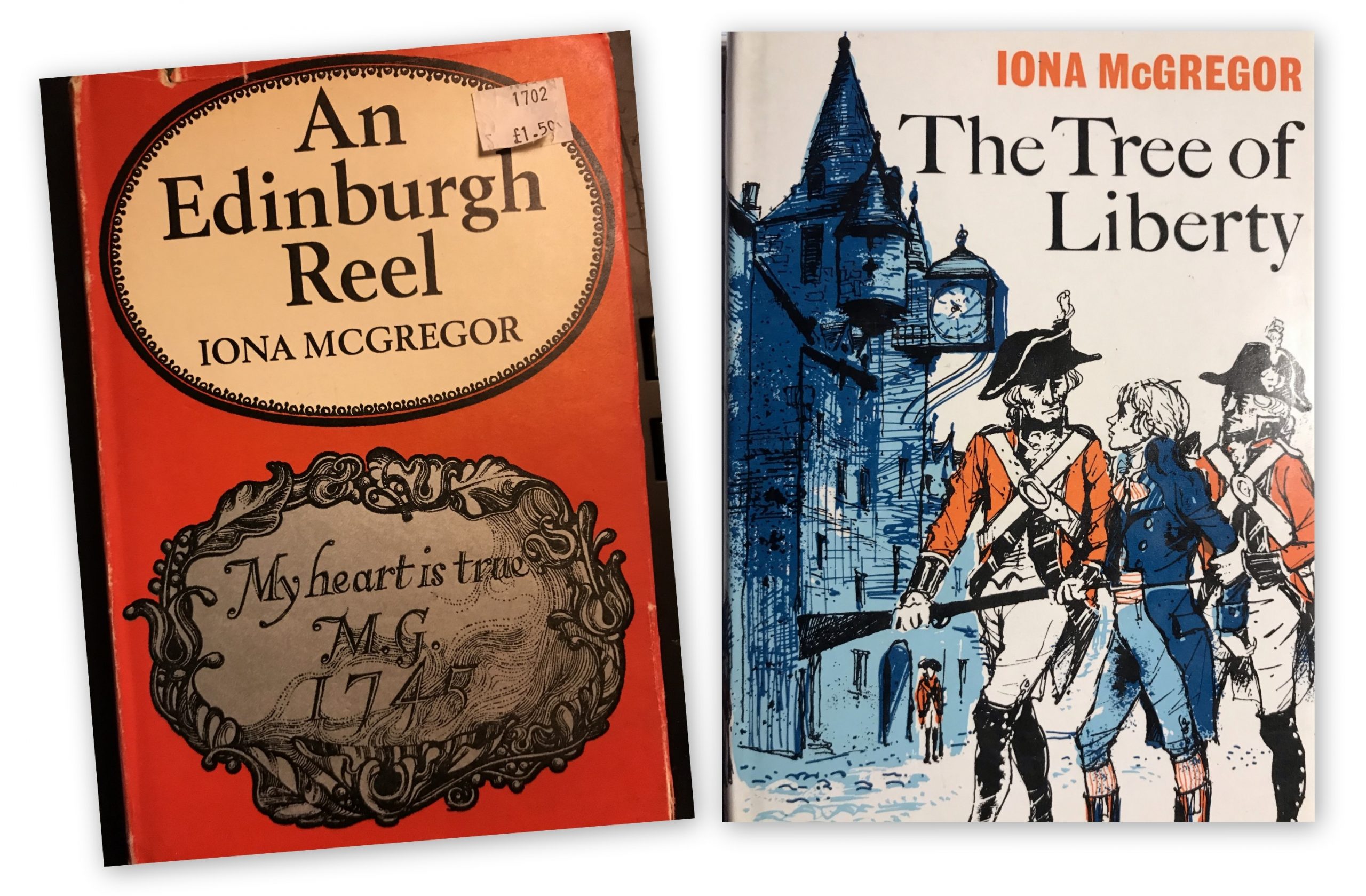

At the same time, she also began to write her young adult historical novels. They were influenced by the prolific children’s writer Rosemary Sutcliffe. They had no queer content, she said, because the publisher made it clear to her that that would never be allowed.

Two of the novels, the ones she felt were the best, were set in Edinburgh: An Edinburgh Reel and The Tree of Liberty. The latter deals with the effect of the French Revolution in Edinburgh, where there were (mostly now forgotten) radical agitators and violent riots, and the book may have a clue to her life after her relationship ended.

Being a rebel is dangerous, but it can also be necessary for survival. The sister and brother in The Tree of Liberty are on opposite sides of the question. Caroline keeps her head down but reads, thinks and looks outward as hopefully as she can. Sandy, her brother, takes part in rebellion and barely escapes with his life – and doesn’t learn his lesson. As the story ends, he is on his way to revolutionary France.

Like Caroline, Iona was a survivor and believed in careful effort rather than impulsive action. The Scottish Minorities Group, which worked for legal reform, also created safe meeting spaces and started a women’s group in Glasgow. Iona became part of it. Making contact with the meeting was complicated, and Iona used the name ‘Chris Campbell’. But despite – or possibly because of? – the elaborate secrecy, she made friends at this time who were still close to her years later.

In Edinburgh, she worked in another SMG women’s group, founded by Ruth Schröck. She also worked as a Befriender on the Gay Centre Switchboard in Broughton Street, listening to queer people talk about the choices and dangers everyone faced in those days.

She did shifts in person at the Gay Centre, introducing women to the group and the scene in the city. She used her own name, met dozens of people week after week and could easily have been outed at work. But it must have made a difference to lesbians who arrived at the centre to meet a woman who was hospitable, well-read, funny, a cat lover, a traveller, a walker and a writer.

Free to write

She left the centre in 1980 and in 1985 she finally gave up her teaching job. She was not outed, but apparently small things built up and the time came to leave. So she was finally free to write the fiction she had always wanted to write, and Death Wore A Diadem was the result.

The novel was based on a long trawl through libraries and manuscripts – in the 1980s, a far greater task than it would be today. Recent scholarship by Rosy Mack has uncovered Iona’s correspondence with her editor at The Women’s Press, Jen Green, which shows that her research included a tremendous amount of detail and speculation about lesbian relationships in 1860. The letters even include diagrams of the school and the characters’ movements within it.

The novel was published by St Martin’s Press in the US. Reviews still turn up in books and blogs on lesbian writing, including The Art of the Lesbian Mystery Novel by Megan Casey and (Re)recovering Victorian Queer History by Rosy Mack on The Activist History Review website.

Iona apparently planned a sequel, or many sequels. The stories of Christabel and her lover, Eleanor, seem to be at their very beginning as the novel ends. James McLevy, a real life Edinburgh detective and crime writer, probably had a further part to play as Christabel’s friend and fellow sleuth.

Later life

But Iona discovered that she could write study guides which paid far better than detective fiction. And there had always been much more to her life than writing.

She travelled and had a large circle of friends she entertained regularly. She learned DIY and was never without an elaborate project. She acquired so many books that, when she moved into a care home later, they were removed by the vanload. ‘There are real gems in these boxes,’ said the librarians at Glasgow Women’s Library, who received the feminist and lesbian books. ‘Some of them are amazing.’

Iona probably also liked the variety of the better-paid writing she was doing, in addition to the study guides: it ranged over many subjects and required much research. As a writer, she was an adventurer.

She also returned to teaching with the University of the Third Age and was a founding member of the AD Group – which had two names for different occasions, Anno Domini and Aged Dykes. She had always been her own kind of lesbian, and she lived her own kind of old age.

This was a not always straightforward. She said that the struggles of her early life had given her ‘a weight, a social guilt’. ‘As she got older,’ said her friend Marsaili, ‘the physical, mental and emotional consequences of living with high levels of anxiety became harder and harder to manage.’

Nevertheless she lived to be 92 and passed away earlier this year at Edinburgh Royal Infirmary, to the sadness of her friends and her readers.

At her funeral in Edinburgh, Marsaili spoke about her and thanked her for her kindness to young newcomers at SMG, her intelligence and courage, and for ‘showing that another life could be lived.’

That life carries on in her novels.

Please feel free to leave a comment about your memories of Iona and the books you’ve read.

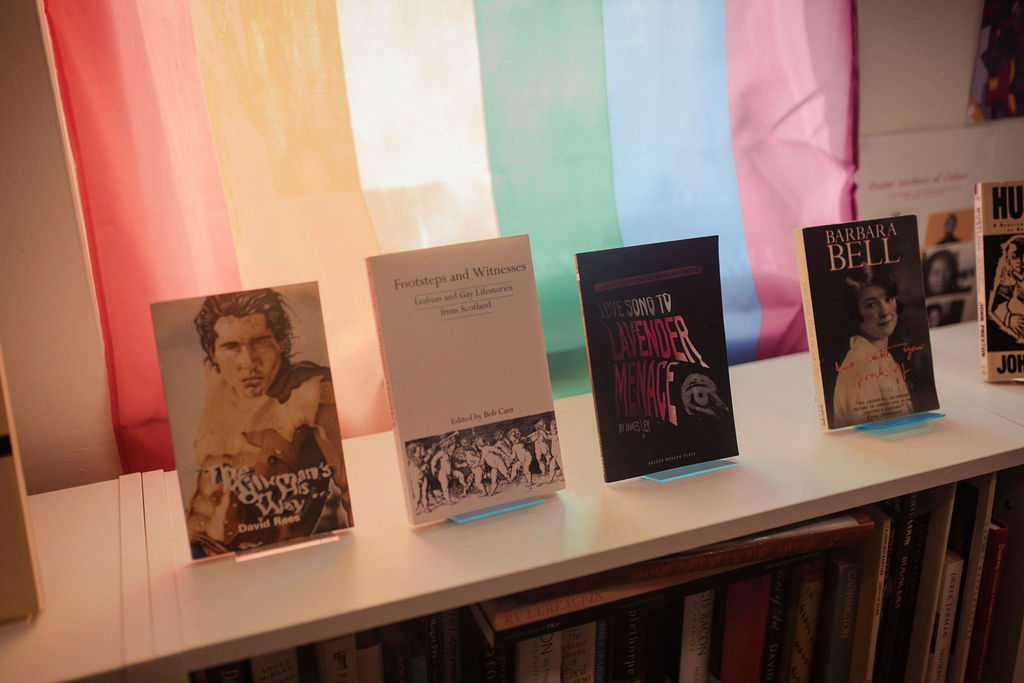

[Iona’s Death Wore a Diadem, An Edinburgh Reel and The Tree of Liberty and Bob Cant’s Footsteps and Witness are all part of the Lavender Menace Queer Books Archive. Iona’s work also features in our video Unsung: the queer books that tell our lives.]

Leave a Reply