Tag: #queerarchivists

-

Three Writing Lives

Our second online event Conversations with Writers took place on Thursday 2 September. Playwright Jo Clifford and novelist and short story writer Ely Percy were in conversation with Eris Young.

-

Du Maurier’s Rebecca and Queer Culture

Why has Rebecca always had a reputation as a queer novel? Generations of gay men have declaimed the first line, spoken by Joan Fontaine in the 1940 film: ‘Last night […]

-

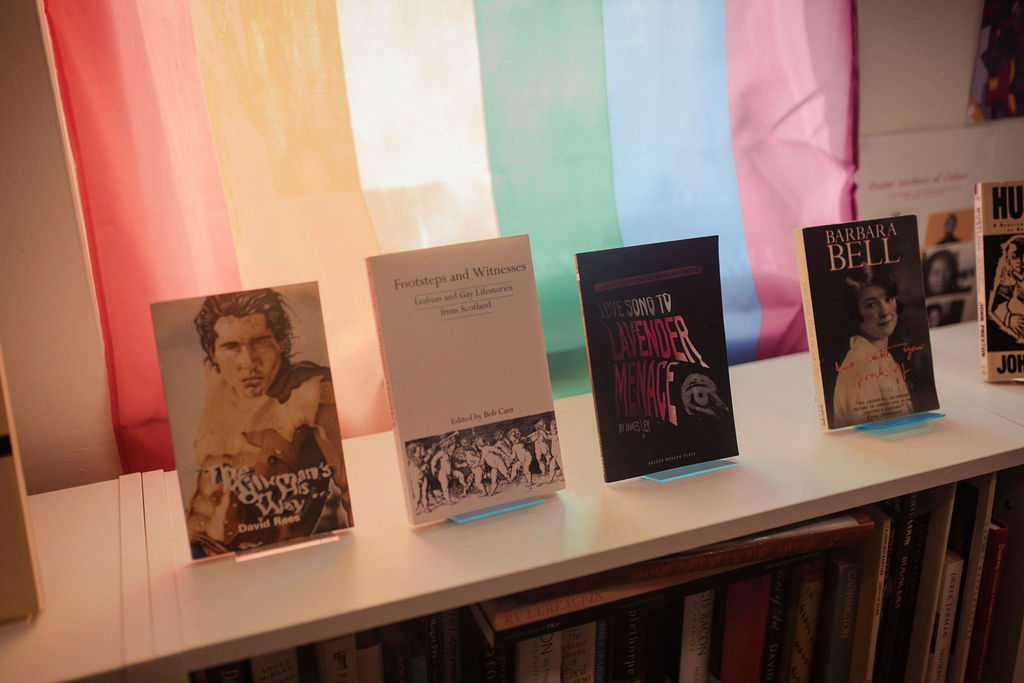

We want your books

Lavender Menace’s queer books archive is growing. We are cataloguing several recent donations, including one from LGBT Health and Wellbeing, and making some exciting finds. We’re always looking for out […]

-

Rebecca by Daphine du Maurier

Rebecca by Daphne du Maurier.Gollancz, 1938; Virago (present publisher). Last night I dreamt I went to Manderley again… Rebecca, Daphne du Maurier’s best known novel, has never been out of […]