Blog

-

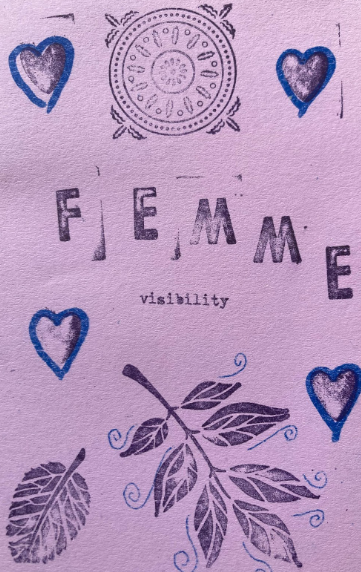

Lavender and Menaces

The clothed lesbian body as a tool of resistance, the sapphic significance of purple, and the making of the modern-day femme To celebrate lesbian visibility week this year, I decided […]

-

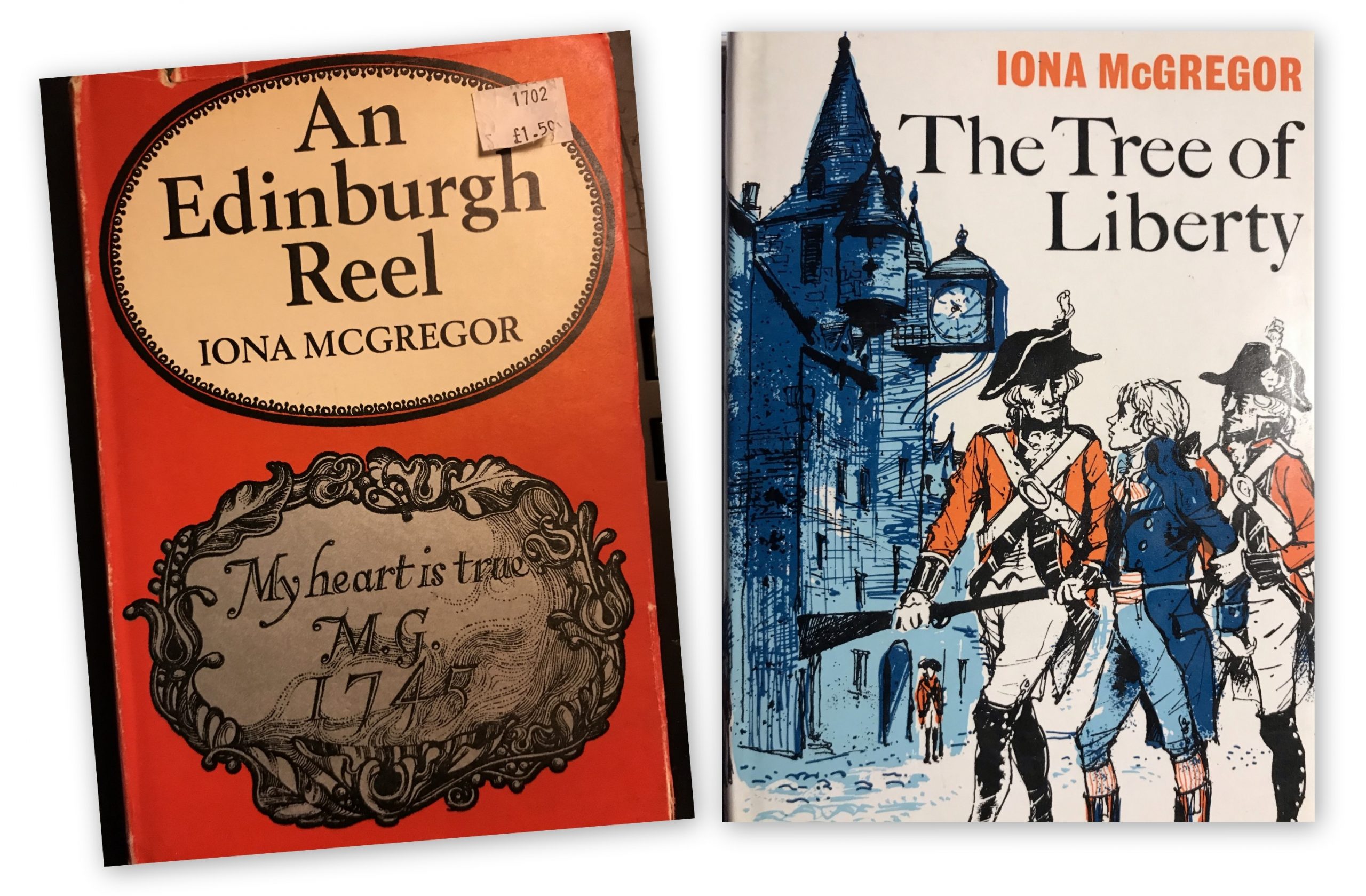

Welcome to our blog

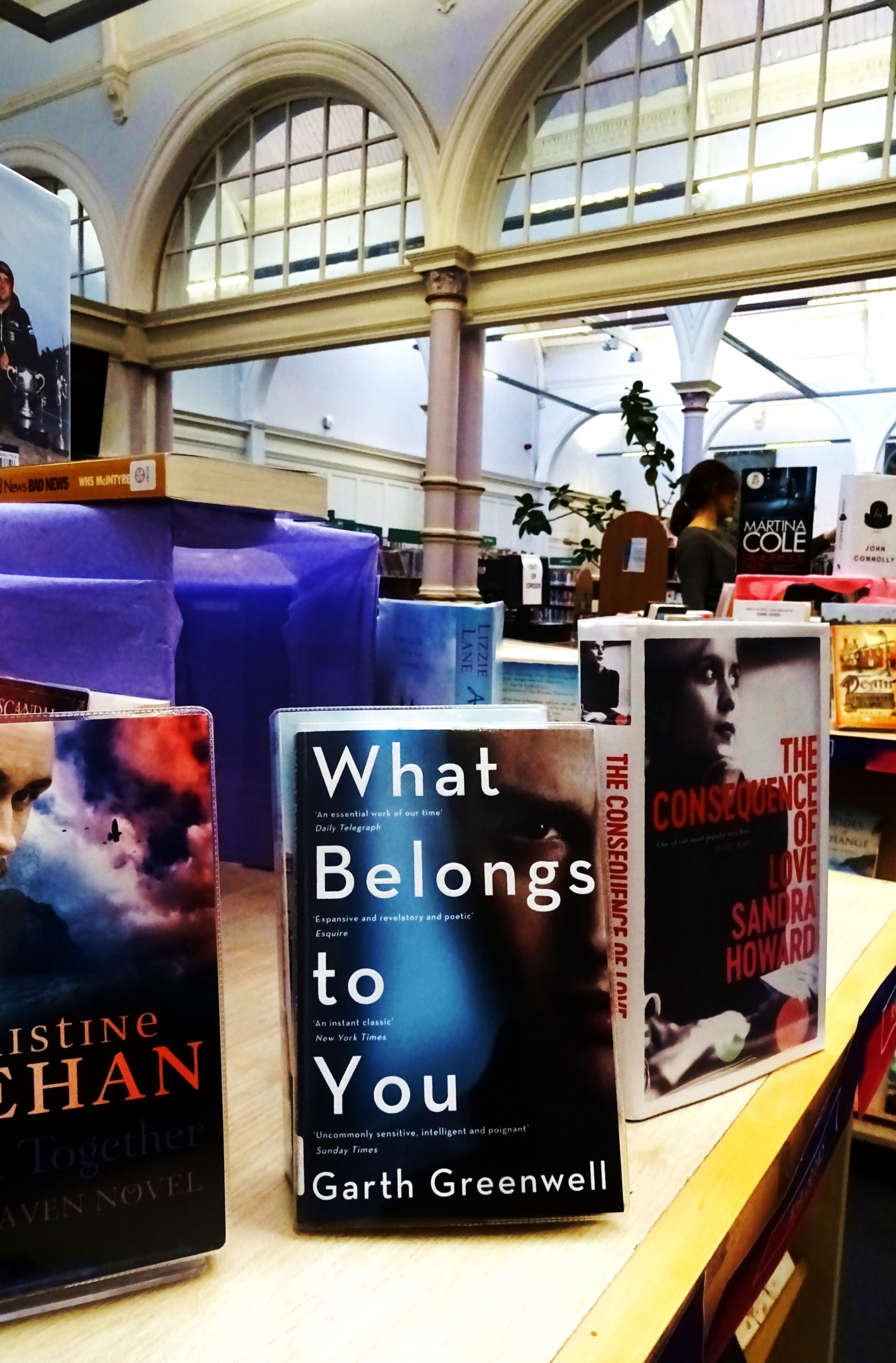

We’ve already started blogging about the books in our growing archive – found in our own and friends’ collections and secondhand shops. And we invite you to join us.

-

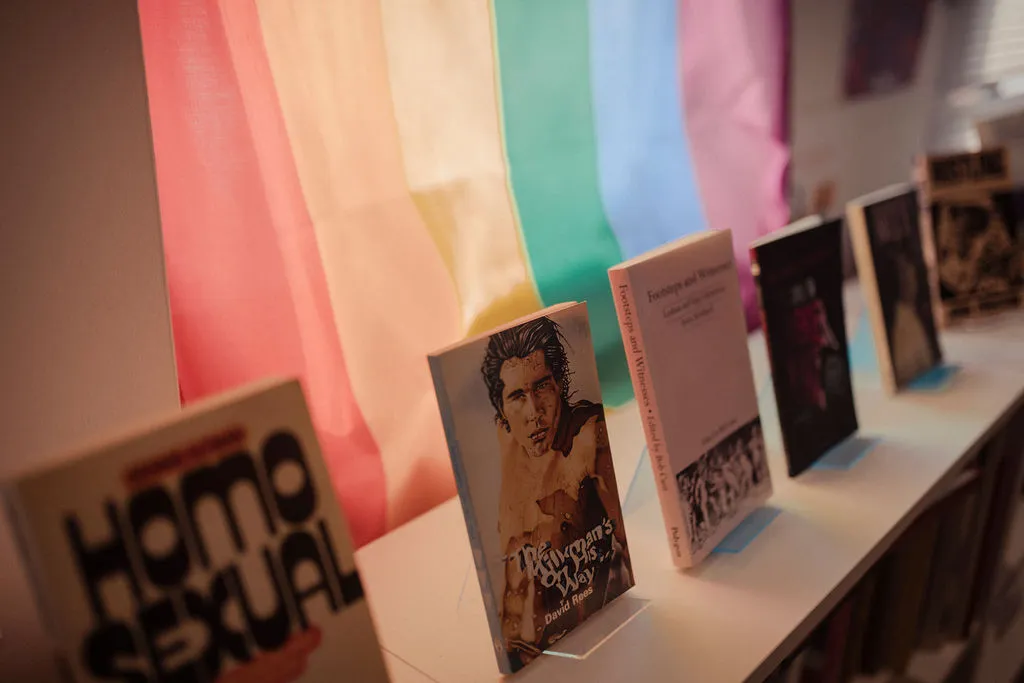

Menaces in Colour

Cartoonist Kate Charlesworth and Lavender Menace Queer Books Archive launch their new range of cards and bookmarks!

-

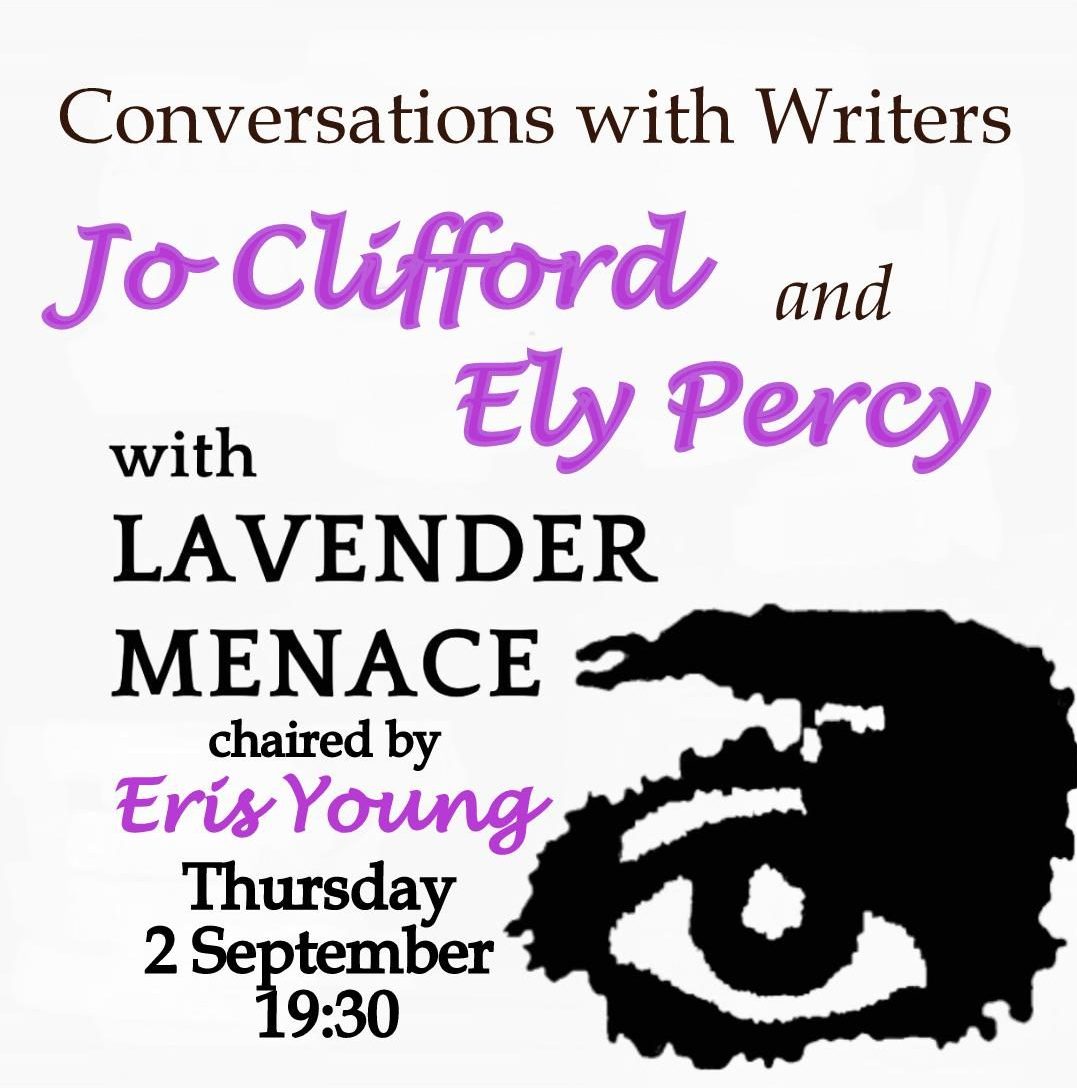

Three Writing Lives

Our second online event Conversations with Writers took place on Thursday 2 September. Playwright Jo Clifford and novelist and short story writer Ely Percy were in conversation with Eris Young.

Got any book recommendations?