Peter Parker is an acclaimed author of biographies and histories, with a particular focus on twentieth century queer writers such as Christopher Isherwood and J R Ackerley. His latest book is Some Men in London, a two-volume anthology of writing about gay life in the English capital between the end of World War Two and the partial decriminalisation of homosexuality in 1967.

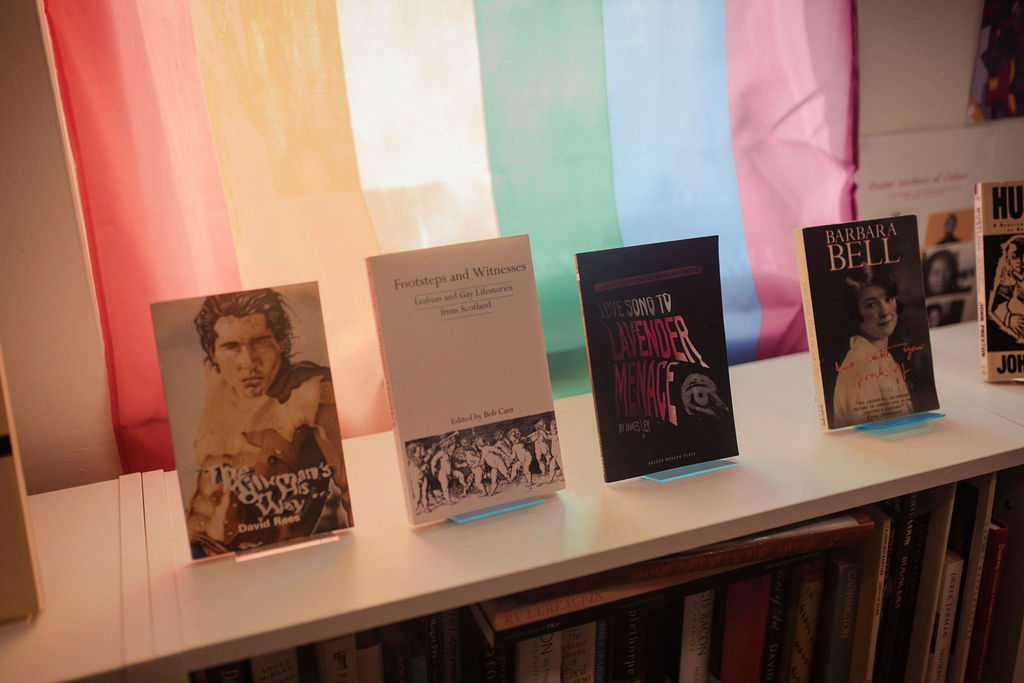

In June, Peter was in Edinburgh to promote the book and kindly agreed to drop in to the Lavender Menace archive to chat about queer lives and literature and many other topics close to the hearts of the Lavender Menace team.

In this second blog post, Peter and Lavender Menace co-founder Sigrid Nielsen discuss iconic gay writers Christopher Isherwood, J R Ackerley and E M Forster, the art of writing biographies, and the need for faith in the future.

If you haven’t already, you can also read the first blog post where we discussed police raids, moral panics and the power of queer literature.

The interview has been edited for length and clarity. Trigger warnings: homophobia, mental health, suicide.

Sigrid Nielsen: Something that intrigued me was that in your biography of Isherwood you say that first he was telling a story with a certain amount of fantasy, in Lions and Shadows. But then when he came to write Christopher and His Kind not all of that is any more realistic than Lions and Shadows. And, when I read Christopher and His Kind in the 70s, one of the things that made me happiest about it was he’s telling the truth—he’s saying these things nobody is allowed to say. I was in my twenties then and I read it standing in book shops, keeping an eye out for the staff, and I would come back every day and read it for a while. But, of course, it never occurred to me that perhaps he was writing it in a way that, well, that made him look better—just changing the story for his own reasons—and I wondered if there’s more you can say about that?

Peter Parker: Well, I think a lot of the things he changed were for very good reasons. They were not to hurt people, particularly what he wrote about his younger brother, who had clearly had some sort of mental health issues. He had a major row with his mother when his brother was caught exposing himself and that didn’t get into the book. So you have the row, but there’s no real explanation—or he gives a different explanation that seems to be perfectly honest.

And of course, Isherwood had spent his entire career turning his own life into fiction, until at the end he then wrote the nonfiction books. And I think, you know, old habits die hard and there was a—I think it’s a letter to John Lehman—where he says, you know, it’s so bloody hard writing nonfiction because facts keep tripping you up. And, of course, the novelist can just change them.

And I think that that is one of the reasons that for Some Men in London I’ve only taken material that was written at the time. So, I don’t have memoirs that were published after 1967, and one of the reasons is that there are some very good books—and some much, much later—but the past is a different country and, looking back on it, you’re looking back from a different perspective. You’re older, you’re remembering some things, you’re not remembering others. And all that’s perfectly fine, but if you want a kind of documentary experience, which is what I want the book to provide, then I think you have to stick absolutely to that period and have no looking back, even if it meant having no J R Ackerley’s My Father and Myself, or no Quentin Crisp, The Naked Civil Servant.

I don’t want to be too hard on Isherwood, but My Guru and His Disciple, where he absolutely fudged evidence to make, in particular, the Swami Prabhavananda look better than he did and be much more liberal about homosexuality—it is more or less a hagiography. But I thought that was a bit more disturbing. I mean, I don’t mind if he fudges a few things about his family in Christopher and His Kind. And it is true that Christopher and His Kind is a sort of landmark book, because I remember buying it when it came out. Actually, by that time I knew a lot about Isherwood because I’d been introduced to [his work] by someone at school: a fellow schoolboy said, ‘Here’s Mr Norris Changes Trains. I think it’s the sort of book you like’, and indeed it was. So, I did immediately leap on Christopher and His Kind and I loved it.

The trouble is, if you’re writing a biography, you read these books again and again, and sometimes they’re even better than you remember, and sometimes you get more worried about them and say, ‘But hold on a moment. I’m not sure this is right.’ It’s like when you write a biography, you actually get to know your subject probably better in some ways than their partners, their parents, their siblings do. And that’s a very curious position to be in. And there are things where you have to ask people who are still alive, and you’ve got to be quite careful because you may be revealing something that they weren’t supposed to know.

But the comic side of that is that Stephen Spender, in his old age, he’d been at a tutor at my university so I knew him from there, and he knew J R Ackerley, so I went to talk to him. And obviously when I did Isherwood, he was a key person. And as I was writing it, he’d occasionally ring me up and say, ‘Peter, do you happen to know what I was doing in June 1932?’ And the worrying thing is that I usually did, and that seems to be a slightly awkward position to be in: that you remember more about somebody’s life than they do themselves!

But I think writing biography is an exploration, you know, however well you think you know someone, you’re always going to find out stuff that you didn’t expect, some good, some bad. And I suppose the probable answer is that I ended up liking Ackerley even more when I finished the book, and with Isherwood it was slightly disillusioning. I mean, I still think he’s a wonderful writer. Not all the books are good. But then why should they be? You know, people have a long career. They’re allowed a couple of duds and even his duds have very good things in them.

SN: He himself was very honest about that.

PP: Yeah, he was, exactly. But you know, it’s no secret that Don Bachardy, his partner, hated my book, and it was just fortunate that we had a contract that said, although I would show it to him and I would take note of anything he said, it was up to me if I cut stuff or not. And it was very fortunate because in fact, what happened, he was so cross he never spoke to me again. So, he didn’t even say, ‘Look, I don’t think this is right’, which was very useful for me of course, but I’m sorry because I didn’t intend to upset him. But as Ed Mendelson, Auden’s [literary] executor, said to me, ‘If you write a book, you’ll never please the widow.’ And I think that’s right: I don’t think you do write for your subject’s friends. You’re writing for a much wider audience.

Apparently, Don had said to someone, ‘Well, Peter obviously hated the books.’ To which my answer was, ‘I don’t.’ I think The World in the Evening is a very poor novel indeed, and I don’t much care for A Meeting by the River, but I champion books like The Memorial, which nobody reads, which I think is a wonderful book. And you don’t spend twelve years writing about someone you don’t admire. I mean, you just wouldn’t. You’d give up. And I know people who have given up. They’ve had ideas for biographies and they’ve given up because either, rereading the books, they didn’t think they were as good as they remembered, or they find out things about them that they didn’t like.

I’ve never—fortunately—been in that position of being particularly upset if I find out things about people I’m writing about and thinking, ‘Well, I’d rather they hadn’t said that, or they hadn’t done that.’ It’s not going to upset me because I think you have to be objective, and what I don’t like is the biographer wagging a finger and saying, ‘At this point he did things that were wrong.’ I tend to use irony and, of course, in America not everybody understands irony. For example, Isherwood could be very misogynistic and very antisemitic. Partly that was his background, partly having a mother he really didn’t care for. But how do you deal with that? And my way was to, as it were, channel Isherwood. So, there’s just a passage that says, ‘He didn’t much care for women’, and then I do a sort of parody of saying, ‘They lead perfectly nice heterosexual boys astray and litter the place with their ghastly shouting, whining children,’ which is really what Isherwood had said. And I thought it’s much better that than me sort of wagging my finger. I think you have to be sympathetic even when people are behaving badly. And it’s much better to just gently, as it were, point the reader in that direction rather than hammering home a point.

Lavender Menace: Do you think the fact that you sometimes write biographies and sometimes write more general histories, does that help you to keep an objective view of your subject when you’re doing a biography?

PP: Yes, I haven’t really thought of it like that. I suppose it does. A history is a very different type of book. It’s much more wide-ranging. I suppose that the new book is rather a mixture of a bit of everything. But there is a fair amount of history and there’s a fair amount of biography along the way.

My book on A E Housman, Housman Country, was really not a biography of Housman, but a biography of A Shropshire Lad, as my agent put it. But there was a biography of Housman within it, and that was very different from doing these nuts-and-bolts, cradle-to-grave Isherwood or Ackerley biographies. But I found that really interesting to write because I was coming from a different angle, and I didn’t have to fill in every bit. The Isherwood was the first one done after he died, and it had, at the beginning, the cooperation of Don Bachardy. I felt that I had to do a really pioneering… people said definitive, but I don’t think any biography is definitive.

As you probably know, Katherine Bucknell has published a new biography of Isherwood. She edited all his journals and we’re doing an event together, which will be very interesting, I think. I haven’t yet read the book because I’ve just been doing this, but I’ve got it with me to read on the train—or read some of it on the train, because it’s almost as long as my biography of Isherwood, which is saying something! We have talked about it about a year or eighteen months ago, when she still hadn’t finished it. We had a very nice dinner at her house, just the two of us, and we started chatting about Isherwood in a way that was completely natural. I think a lot of people were cross on my account when it was announced she was doing [an Isherwood biography]. You know, my book was twenty years old! And it’s Isherwood! Of course there are going to be many more books on Isherwood! I think if someone did another book on Ackerley, I’d be more protective, but it’s less likely. Having said that, no doubt I’ll read tomorrow that someone’s doing a new biography!

But after all this time [Katherine’s] coming from a different angle. She’s American, although she lives in England, and she’s very close to Don Bachardy, which I never was. So, it’ll be a very different kind of book. And she’s a scholar, which I’m not, you know? I mean, she’s a very serious scholar, an Auden scholar in particular and also an Isherwood scholar, whereas I’m a jobbing biographer—and I don’t mean that in a faux modest way, it’s just that if someone calls me a scholar I think, ‘Oh God, it wouldn’t be as much fun if I was a scholar! I’d be worrying all the time!’ I much prefer just to be the person telling a good story.

LM: Yes, academia can be quite pressured, can’t it?

PP: Well, also a lot of academics simply can’t write, so there’s that too!

LM: There is that, yes! But it’s interesting that you say that because I think, from a reader’s perspective, if you read biographies and it’s someone that you’re interested in you’re never going to be upset that someone else is writing another biography. So, looking at it from that perspective, of course there should be others. And it doesn’t detract from what you’ve done or what anyone else has done.

PP: No. Often they’re very complementary and the fact they’re coming from slightly different directions—the actual point where they meet is interesting. I shall be interested, when [Katherine and I] talk, about where we are covering the same ground and where we’re not. Both are interesting.

SN: If you’ve treated this in detail in your Isherwood biography, I’m afraid it’s escaped me but, as you say, finding out something new about gay history is always exciting and I found out in a recent biography of Forster that it was Isherwood who finally persuaded Forster to publish Maurice, when his gay friends for many years had warned him not to—and the gay friends were worse about it than the straight ones. I hate to think what that probably did for his own view of himself as a writer—it probably broke his heart in a way.

PP: Yes, I think Maurice is a much better novel than people say. I wrote a piece about it for the TLS for the fiftieth anniversary and, doing research for that, you could see that when Maurice was published everybody was saying this is a third-rate work. I mean, in all sorts of ways, it’s not as sophisticated as some of his other novels but it’s so heartfelt. When it came down to it, a lot of the reviews that said this is no good, they were basically saying, no, they were pretending that gay men don’t have these sorts of relationships. There was a great deal of prejudice amongst the critics, and some very distinguished critics who ought to have known better.

As far as I remember, Forster left the manuscript, or he left the copyright of Maurice to Isherwood, who he’d known since the 1930s and who he saw as, sort of, the future. There’s a very good description in Christopher and His Kind of the young Isherwood going to sit at Forster’s feet—I don’t think literally, but more or less—and it’s almost like one of those genre pictures of handing on the baton.

SN: Someone should paint that!

PP: Yes, exactly! I remember I was at university when Maurice was published. And my tutor, my gay tutor, coming and brandishing a copy. And the great excitement of this novel coming out.

And everybody said, ‘Oh, it’s so unrealistic, these people going off together, this gamekeeper and this middle-class man.’ Forster makes it all sound so easy, and of course it wouldn’t have been. And there was the problem of the date of it because there would have been the First World War, which would have put paid to whatever plans they had. I mean, I suppose Maurice could have gone off to war, and taken Alec Scudder as his batman. That would be possible.

But Forster says in the afterword, ‘It was essential for me that it should have a happy ending. I wouldn’t have written the book without it.’ And I think that’s an article of faith. People who sneer at the book and sneer at him for not publishing it just don’t understand the sort of pressures [he was under].

Isherwood himself said that he got fed up with gay novels where they always end up in suicide or accidental death. Even Gore Vidal’s The City and the Pillar, in the original version, ends with him murdering his former lover, and then he changed the ending. And when you read the reviews a lot of them say it’s unrealistic. They’re basically saying, we know what gay fiction is like. We know what the ending is like. Someone’s going to throw themselves under a train. Someone’s going to be run over. Somebody’s going to commit suicide. They’re going to part.

And Forster wanted to show that actually it was possible [to have a happy ending]. He believed in it, and his whole life, there is so much in what he wrote about overcoming these sorts of obstacles, and about that optimism, that faith, that I find very touching, and that is something that should be celebrated.

LM: There’s almost a sense that he was ahead of his time. When the book was published I think it came out at a time where there was maybe a hunger for those kinds of stories and, later, when it was made into the Merchant Ivory film, I was a teenager and I know it made a huge impression on people of my generation because it was showing that, you know, there were hardships and there were difficulties, but there is also this very touching love story—and it has a happy ending.

PP: Yes! And also, in the actual book, there are just brilliant bits. I mean, the ending where it’s Clive working out how he’s going to lie about everything, and the bit where Alec and Maurice, they come together in the boat house—which, again, people joke about and say, ‘How silly!’—but Alec says something like, ‘Well, that’s it.’ And it’s wonderful. It is a sort of faith in the future, and we all need faith in the future!