Guest blogger Dr Sarah Sloane investigates the elusive story of William Greenfield, disgraced Professor of the University of Edinburgh and minister at St. Giles Cathedral.

There was a certain grave Divine,

Esteem’d as wise as Mentor;

Each Sunday did in Pulpit Shine,

But Bugger’d his Precentor.(From The Lion in Tears: Or, the Church’s Lament for Dr. Greenfield, an anonymous ballad published in England in 1824.)

Twenty years ago I was researching early rhetoric professors at University of Edinburgh. Between the biography of Hugh Blair, the first Regius Professor of Rhetoric and Belles Lettres (established in 1762), and that of Andrew Brown, the third Regius Professor of Rhetoric, was a footnote explaining that the second Regius Professor of Rhetoric, William Greenfield, fled his professorship at Edinburgh and his position as a minister at St. Giles in 1798. He lived for the rest of his life under a pseudonym in exile from Scotland.

That’s my guy, I thought, closing the book. The heck with Blair and Brown. I’ve been doing research on William Greenfield ever since then, publishing an article here and there, and giving many presentations about him. But this is the first time I am writing for an audience that might conjecture with me, who might be able to discern what, precisely, William Greenfield did when he “ate turd” rather than enjoyed the bounteous feast assembled before him, as Alexander Carlyle wrote in a letter shortly thereafter. Together we might make sense of what happened, even though Professor Greenfield’s history has been muddled or erased in the last 227 years. But there is evidence to suggest that he was caught in a gay relationship. The following account is what we know about him so far, but readers are invited to speculate with me about what, precisely, his crime might have been.

In 1798 Professor William Greenfield (1755-1727) was a prominent citizen of Edinburgh––minister of Edinburgh’s High Kirk of St. Giles, Regius Professor of Rhetoric and Belles Lettres at Edinburgh University, recent leader of the Scottish Assembly, and member of the Mirror Club, the Harveian Society, and the Aesculapian Club. He had a high profile and lived on Webster’s Close near other luminaries and literati of the time.

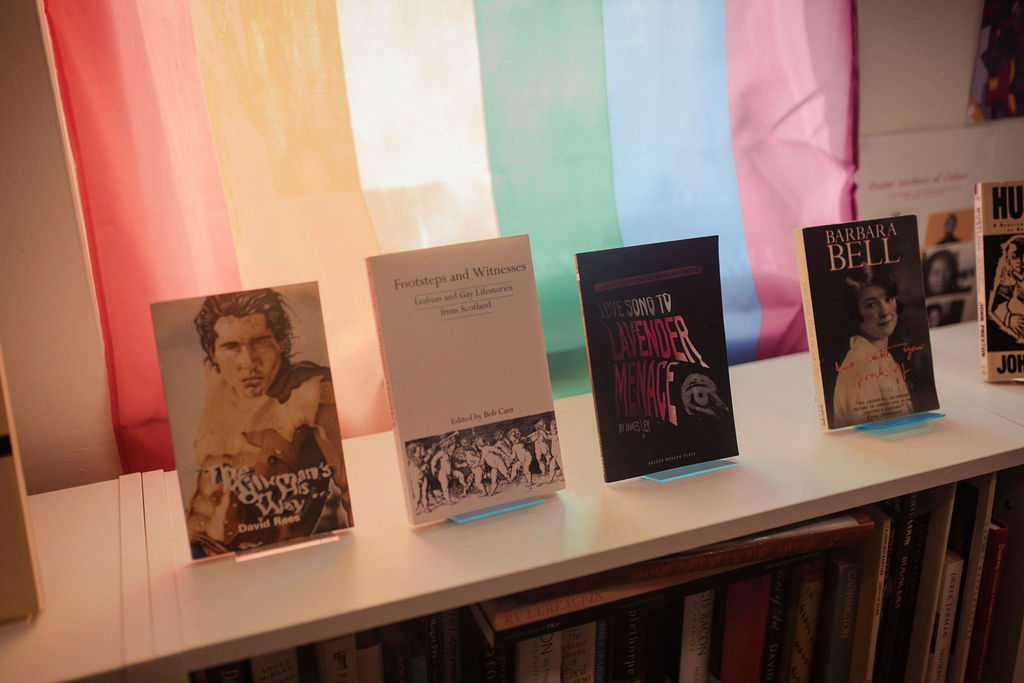

Photo by David M. Gray via Flickr

A few days before December 20, 1798, Greenfield performed an act so “heinous” according to church records (which do not say what the act was) and so public, that he fled from Edinburgh to Corbridge, England, where he and his family changed their last name to Rutherford. A week after he fled, he wrote a letter to the Presbytery in Edinburgh and resigned his position as minister. Soon he was formally excommunicated by the Presbytery, as well as had his professorship at Edinburgh University formally terminated and his academic degrees revoked. Hiding from his creditors as well as the Edinburgh mob, for the rest of his life Greenfield scraped together a living by authoring a book anonymously, and writing reviews and articles under various pseudonyms.

William Greenfield married Janet Bervie (who, like her husband, assumed the name of Rutherfurd after the scandal) on November 22, 1782. Greenfield and Bervie had six children together between 1786 and 1794. He named his firstborn son Hugh Blair Greenfield, after his rhetoric professor at University of Edinburgh.

Sir Walter Scott was a friend and Robert Burns was an admirer. A few years before the scandal, Burns wrote:

Mr. Greenfield is of a superior order.––The bleedings of humanity, the generous resolve, a manly disregard of the paltry subjects of vanity, virgin modesty, the truest taste, and a very sound judgment, characterize him. His being the first speaker I ever heard is perhaps half owing to industry. He certainly possesses no small share of poetic abilities; he is a steady, most disinterested friend, without the least affectation of seeming so; and as a companion, his good sense, his joyous hilarity, his sweetness of manners and modesty, are most engagingly charming.

That Greenfield was held in high regard by his peers at the church and university before 1798 is underscored by his participation in social clubs. The Mirror Club met in Purves’ Tavern in Parliament Close. His other two clubs, likewise selective, met not far away in taverns along the Royal Mile. A note penciled in the front of his son Andrew Rutherfurd’s copy of Greenfield’s book states, “Dr. Greenfield lived in a large self-contained house at the foot of Webster’s Close, opposite the reservoir on the Castle Hill” (roughly where Boswell’s Court and The Witchery are today).

In their meeting notes of December 20, the Church Presbytery accept a letter of resignation from Greenfield. They also excommunicate Greenfield because “a violent fama clamosa” had prevailed against him for several days in the city. The records state that Greenfield had committed “a Sin peculiarly heinous, and offensive in its nature.” They write that Greenfield’s letter of resignation “amounts to an implied confession, that he is so far guilty of the sin, of which he is accused by the voice of the public, as to render him unworthy to continue in his present charge, or to profess the character of a Minister of the Gospel.” The record calls this “a melancholy occasion.”

At the same time, in Faculty Council minutes from University of Edinburgh, we read that the Council voted to revoke all of Greenfield’s academic degrees, with one member abstaining. This abstaining faculty member said that he thought Greenfield suffered from “satyriasis” (a disease that aligns with nymphomania, or excessive or uncontrollable sexual desire). The Horn papers at Edinburgh University Library include a note from two of Greenfield’s colleagues saying that he suffered from “appetitive insanity.” As mentioned above, in Alexander Carlyle’s correspondence he mentions Greenfield, asking why such a man would “eat turd” when other joyous feasts were available. And Grant’s history of University of Edinburgh states simply that Greenfield was afflicted with “an aberration of intellect.”

Three Edinburgh newspapers, The Edinburgh Advertiser, The Caledonian Mercury, and The Edinburgh Evening Courant, published the same remarks on December 28, 1798:

The Presbytery accepted Dr. Greenfield’s resignation of [his] office, and in consequence of certain flagrant reports concerning his conduct, which his desertion of his charge and his quitting this country seemed to preclude the Presbytery from considering as groundless, they unanimously deposed him from the office of the Holy Ministry and laid him under a sentence of Excommunication.

Again, though, we read no words about what, precisely, Greenfield may have done. The reports are secondhand and obscure. The bawdy ballad that opens this blog claims that Dr. Greenfield “bumbuggered his precentor.” (The precentor likely would have been a young man who led the congregation in singing or prayer.) The same ballad even suggests that Greenfield may have had sex with barbers:

[Greenfield] was the Church’s prop and stay,

Penn’d a’ her sage addresses,

But yet forsook God’s holy way

And f-d in barbers a-s.

A nineteenth-century book, Sexual Life in England, notes in a paragraph that

Mr. Greenfield, one of the most respected ministers in Edinburgh, and like many Scottish priests in receipt of a small income, decided to increase it by establishing a boarding house for university students. He was taken in the act of unnatural sexual intercourse with one of these young men. For the sake of the reputation of both parties, the affair was hushed up and it was treated as a case of mental disease. Greenfield renounced his position and spent the rest of his life in retirement under nominal supervision.

These are not mutually exclusive claims. However, Greenfield having had sex with a boarding student is not as persuasive an account as him having “buggered a precentor.” Contemporaneous correspondence gives no hint that he was supervised after his mysterious crime. Given whatever happened aroused the whole city’s ire, a far more public crime is likely to have been committed than having sex with a bedmate, which itself may not have been an infrequent offense, given students slept two to a bed with other students, and soldiers slept double in beds as well.

Why would Greenfield run so quickly? Perhaps because he was terrified of being confined to the stench and grime of the Old Tolbooth and, eventually, hanged. Before 1785, Edinburgh executions were held in the Grassmarket, or occasionally Mercat Cross. But after 1785, they were typically held on the west side of the Old Tolbooth, where there was a gallows and room for the public to observe the hangings. Greenfield would have walked by the Old Tolbooth every Sunday on his way to church. He may have known what could await him.

When Greenfield fled, England, Scotland, and Wales were still under An Acte for the punishment of the vice of Buggerie (passed under Henry the VIII in 1533) as they were until it was replaced by Offences Against the Person Act of 1828. Sodomy was still punishable by death in Great Britain until 1861, with the passage of a new version of the Offences Against the Person Act. As readers will know, homosexuality remained illegal until 1980 in Scotland. Other late eighteenth-century British homosexuals decamped to France, where the French Revolutionary penal code issued in 1791 decriminalized sodomy. Greenfield may simply have wanted to avoid the punishment of hanging or the pillory, the two most common punishments for “sodomy” and “sodomitical assault.”

The pillory, or stocks, which Greenfield may have feared, were a very dangerous punishment. Men and women who were sentenced to an hour in the pillory sometimes died there. After the criminal’s arms and head were locked in place in wooden stocks, she or he would be assailed by crowds, sometimes of thousands, who threw rotten fruits and vegetables, dead cats, spoiled butcher’s meat, and sometimes stones. A lesbian woman was blinded in the pillory in England. Following an occasion when two men were convicted of sodomy and one or both were killed by an English mob throwing things, Edmund Burke spoke in parliament against the practice. When “sodomites” were pilloried, women were often given pride of place in “the front row” of the crowd, pelting the men violently because their sin was seen as a special affront to women. In the same ballad quoted above, the author says he wishes Greenfield would be “drown’d in women’s piss.”

In addition to book reviews published under the names Greenshields and Richardson, in 1809 Greenfield anonymously published a book based on his lectures at University of Edinburgh, calling it The Sources of the Pleasures Received from Literary Compositions. (In 1813 he published a second edition with a few alterations, including a new mention of the hazards of laudanum.) His book’s section on Pity reverberates given his own life:

The most interesting cases are those, in which a person of real goodness has unhappily been ensnared in guilt. The anguish of shame and remorse, with the despair of ever rising from his present degradation to the fair fame and consideration which he once enjoyed, are sufferings so cruel and hopeless, that they entitle him, at least, to our pity. In real life, the world, and even his friends, may sometimes withhold not only their countenance but their pity where the phrensy of a moment may stain indelibly the purest character.

Thirteen years later, the transcript of the 1811 Woods and Pirie trial (about two school teachers accused of lesbianism) references “The Greenfield Incident,” which a witness characterizes as the case of a clergyman from Edinburgh who was guilty of gross immorality and shameful indecency. She states that it was well-known that the clergyman and his whole family was “mad.” Later in the transcripts, when the clergyman is revealed as Greenfield, he is held up as an example that even men of great integrity can fall into the “taint of insanity,” and into an unnatural lust. The judge says of Greenfield, “It is well known that the clergyman alluded to, and others of his family, were mad; and instead of being remarkably pious, it is well known, that the most remarkable feature in his character was, that his principles and opinions were totally inconsistent with the profession he had adopted.”

Greenfield spent the rest of his life in Corbridge, England, far from his former society but still championed by the likes of Sir Walter Scott and Lord Lansdowne. Near Greenfield’s death his son, Andrew Rutherfurd, writes in a letter that his father is in “excellent health and spirits,” but sometimes “fluttered and confused.” Greenfield and his wife, Janet Bervie Rutherfurd, died just eight days apart: June 28 and June 20, respectively, in 1827.

Any history is a matter of assembling shards, and in the case of Greenfield’s life, the shards are few. What did Greenfield do? All we have is a story that can barely be reconstructed through fragments of correspondence, church records, newspapers, Faculty Minutes, a book he published about rhetoric, a reference in a court trial 13 years later, and a bawdy ballad (quoted above). His past has largely been erased. I have been trying to piece together what happened in “The Greenfield Incident” for years, and this is the best I can do. I look forward to hearing readers’ ideas.

Leave a Reply