‘Live! Live the wonderful life that is in you! Let nothing be lost upon you. Be always searching for new sensations. Be afraid of nothing.’

Oscar Wilde, The Picture of Dorian Gray

‘By the clustered grapes of Dionysus, I swear one day

you will come to know

the name of the Roaring One.’

Euripides, The Bacchae

Lavender Menace volunteer, Michael, explores the queer links between The Picture of Dorian Gray and the Cult of Dionysus.

Content Warning: this article includes discussion of death, homophobia, and incarceration.

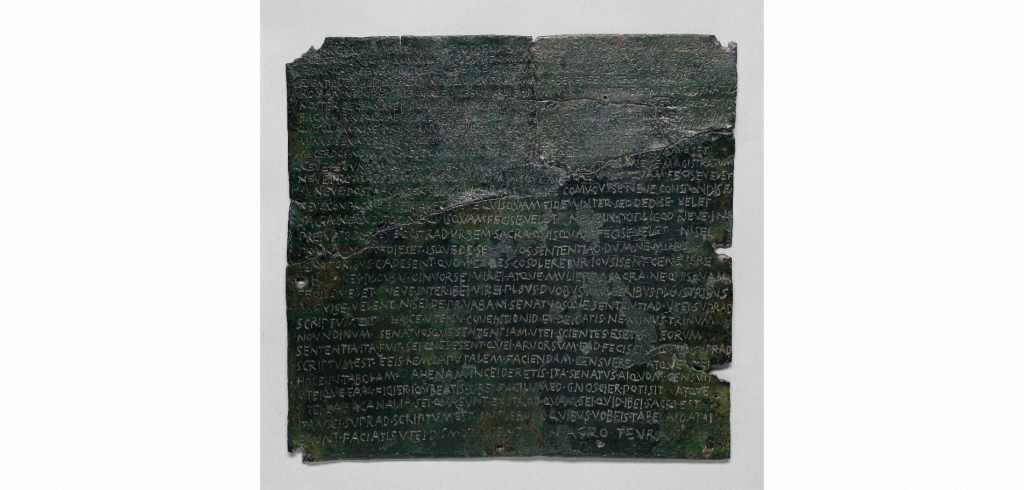

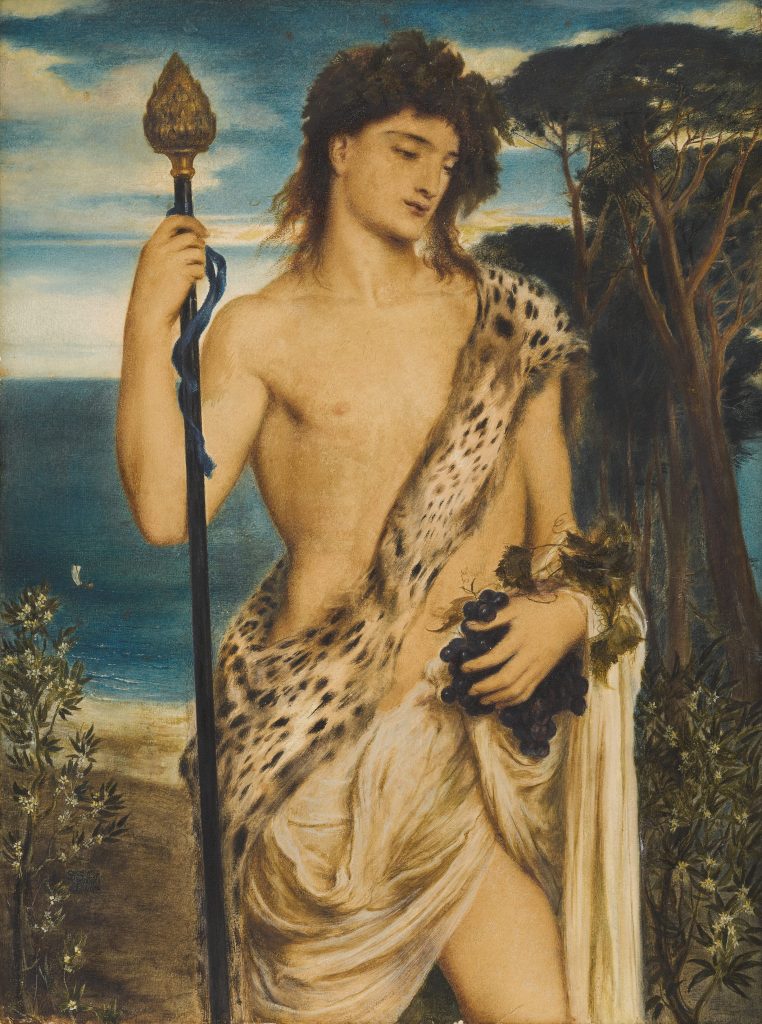

The Bacchanalia

In 1640, during the construction of a palace in the town of Tiriolo in the south of Italy, a bronze tablet was found inscribed in Old Latin. The tablet, which has since been dated to the year 186 BCE, contains the oldest surviving decree of the Roman senate. The decree concerns the Bacchanalia, festivals honouring the Roman god Bacchus — also known as Dionysus, the liberator; god of theatre, wine, fertility, and madness, and details heavy restrictions placed on the festivals; banning the priesthood of Bacchus and the observation of Bacchic rites without express permission from the Roman Senate, all under penalty of death.The Roman historian Titus Livius, better known as Livy, writing around 200 years after this decree, paints a colourful picture of the Bacchanalia. He tells the story of a courtesan who gave testimony against the cult of Bacchus; that those involved in the cult were not above any crime at all, and any who were reluctant to be involved were sacrificed. Men who were very like women were filled with more lust for one another than they were for women, and ‘To consider nothing wrong … was the highest form of religious devotion among them’. Regulating rites descended from the widely practiced festivals of Dionysus in ancient Athens, these enormous restrictions were the first of their kind in Roman culture. These queer, lustful practices, of which Livy claims several thousand people were involved, form elements of Livy’s picture of the moral decline of Rome.

‘To the religious element in them were added the delights of wine and feasts, that the minds of a larger number might be attracted. When wine had inflamed their minds, and night and the mingling of males with females, youth with age, had destroyed every sentiment of modesty, all varieties of corruption first began to be practised’

Livy, trying to make the Bacchanalia sound like a bad thing

The Cleveland Street Affair and The Picture of Dorian Gray

Two thousand and seventy five years after the Bacchanalia were outlawed in Rome — in June of 1889 — a police constable was investigating a theft in the London Central Telegraph Office. During the investigation, the constable discovered a telegraph boy who was in possession of several weeks’ worth of wages in cash. Suspecting him of the theft, the constable took him in for questioning. The boy turned out to have earned the money working as a sex worker for another man he had met through a post office clerk, which led to the discovery of a ring of male sex workers working at 19 Cleveland Street, London. Many of those involved were prosecuted under the Criminal Law Amendment Act 1885, which criminalised ‘gross indecency between males’. Numerous members of so-called high society were implicated in the scandal that followed, with even the Prince of Wales’ eldest son, Albert Victor, rumoured to have been involved. In less than a year the scandal reached the point of allegations being made in parliament that high ranking members of the government were trying to hush it up. Only four months after these allegations were made, on the 20th of June, 1890, Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray was first published in the United Kingdom.

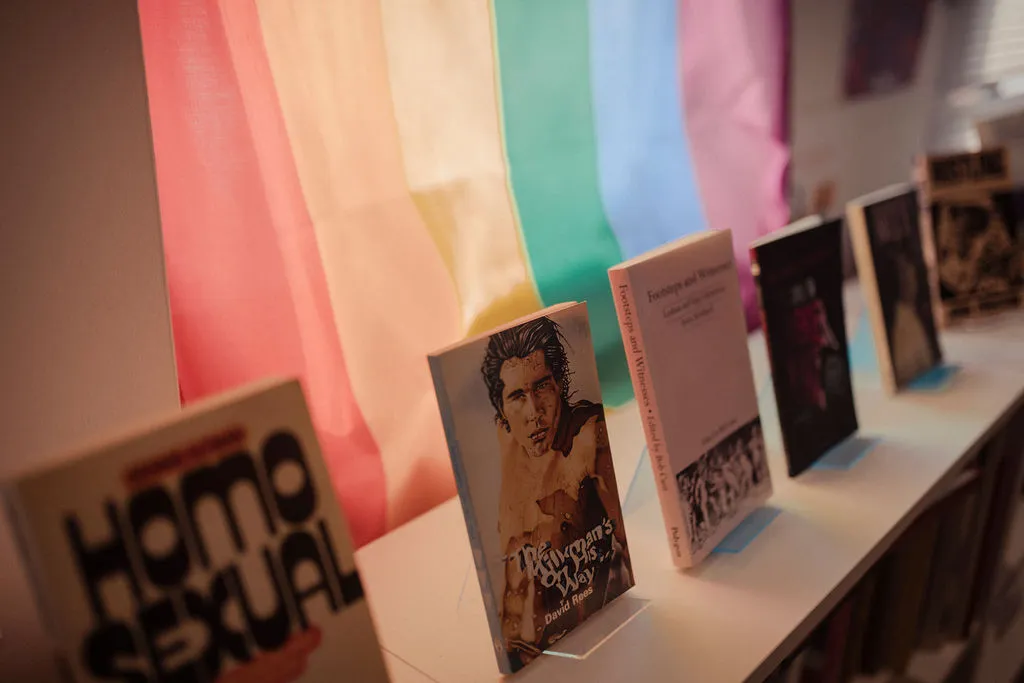

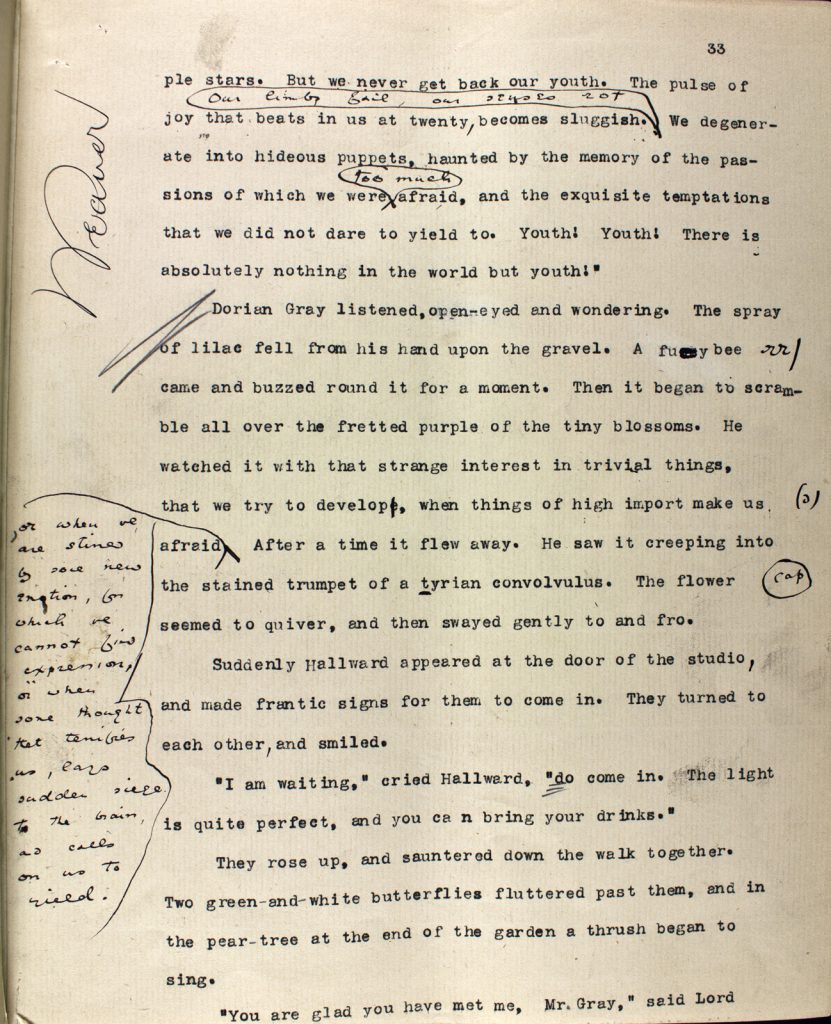

The story (originally published in Lippincott’s Monthly Magazine) was greeted by many with outright disgust, with the Scots Observer’s review clearly referencing the scandal: ‘if [Wilde] can write for none but outlawed noblemen and perverted telegraph-boys, the sooner he takes to tailoring (or some other decent trade) the better for his own reputation and the public morals’. As a result of this backlash, Wilde would censor some of the most homoerotic passages for the 1891 novelised edition of The Picture of Dorian Gray (which remains the most widely published version to this day). This version takes some of the focus away from the homoerotic nature of Dorian’s crimes, and lessens the moral ambiguity of the story, changing details of the ending (which I will not spoil here). This, however, would not stop the prosecution using the Lippincott’s edition against Wilde when he was tried for ‘gross indecency’ in 1895. But even this version was not the most explicit. When the typescript of The Picture of Dorian Gray was received by J. M. Stoddart, the editor of Lippincott’s Magazine, he removed some 500 words from it in order to make it ‘acceptable to the most fastidious taste’, reducing the explicitness of the text.

The typescript edition, which restores Wilde’s original words from Stoddart’s censorship, was published for the first time in 2011, and is now available as The Uncensored Picture of Dorian Gray. One of the major victims of this censorship is the name of the corruptive book that is gifted to Dorian by his friend, Lord Henry Wotton. Lord Henry was likely based on Lord Ronald Gower, a prominent figure implicated in the Cleveland Street affair, and the book which Lord Henry gives Dorian — the yellow covered book of which Dorian is so obsessed that he acquires five different first editions — is a major catalyst in his fall into depravity. The book is named in The Uncensored Picture of Dorian Gray as Le Secret de Raoul (The Secret of Raoul) by Catulle Sarrazin. This fictional title and author references the French decadent movement, which was heavily characterised by a hedonistic pursuit of pleasure, considered poisonous by the Victorians. After reading about Raoul’s depraved adventures, Dorian becomes obsessed with sensual pleasures without regard for his reputation or the reputations of those he debauches. Dorian, possessed by his life of indulgence, partakes in his own Bacchanalia, capsizing his social status to delve into a world of hedonistic physical ecstasy.

Dorian, Wilde, and the Maenads

Dorian Gray’s descent into hedonism mirrors the ritual madness of the maenads, the female followers of Dionysus who formed the majority of his cult. These mad ones would drink wine seasoned with psychedelic herbs, accepting divinely endowed insanity, indulging in feasting, dancing, crossdressing, and sex. Those who would resist this madness would receive the consequences, like the king of Thebes in the ancient Greek play The Bacchae. The play tells the story of the introduction of Dionysus’ cult into the city of Thebes. King Pentheus disrespects Dionysus and refuses to allow his cult in the city, and for this he is torn limb from limb by the maenads. Le Secret de Raoul is the catalyst for Dorian’s own ritual madness, which brought the maenads strength and euphoria. The madness the maenads are blessed with upends social order, and denying it destroys one utterly.From this madness comes another major aspect of the cult: the subversion of social roles. This is seen in The Bacchae, where the two only men who partake in his rites dress in women’s clothes, and the women who worship Dionysus take on the masculine activity of hunting. The cult of Dionysus therefore became a place where those who had little power in society — women, foreigners, slaves, etc. — could gain power over their own lives, at least for a time. These festivals which are centred on the subversion of social order are often explained as a temporary, controlled subversion which allows people with low status to vent their frustrations, but ultimately serves to keep this order stable. It has been said that this is also a function of Gothic literature (a tradition which The Picture of Dorian Gray sits proudly in). Perhaps this is the case with many Gothic novels, and with many instances of these rites, such as the Dionysia — the festivals of Dionysus which were a stable feature of the extremely socially stratified Athenian culture for centuries. This, however, misses the whole picture. In many cases, these kinds of rituals can become places for the socially downtrodden to not just vent their frustrations before returning to business as usual, but come together and find new ways of organising their lives, contrary to the established social order. After all, if all these books and rituals did was uphold the social order, why would the Roman Senate have banned the Bacchanalia? And why would Oscar Wilde have been convicted of ‘gross indecency’, with The Picture of Dorian Gray used against him in his trial? These acts — these rituals, cults, and poisonous books — are truly subversive. They create a microcosm of a new social order which upends oppressive hegemony, threatening it with the liberation of the subjugated. The revelry and madness of the maenads in Rome was truly subversive, and so was the decadence of Dorian Gray.

Beauty as Resistance

In an interview with the photographer Anna Blume, artist and activist Zoe Leonard recounts a conversation she had with fellow artist and activist David Wojnarowicz about making ‘apolitical’ art during the AIDS crisis: ‘I think at that time I felt almost guilty making art, because people were dropping like flies. They still are. And I felt that making art was this incredibly indulgent thing … I remember showing those pictures to David and talking things over with him and he said – I’m paraphrasing – “Don’t ever give up beauty. We’re fighting so that we can have things like this, so that we can have beauty again”. … David was right. You go through all of the fighting not because you want to fight, but because you want to get somewhere as a people. You want to help create a world where you can sit around and think about clouds. That should be our right as human beings.’Without beauty and pleasure; tasting the fruit and cherishing the clouds, we lose our will and grow tired, but more than this, taking in worldly pleasures is in itself an act of resistance when so many seek to deprive us of these joys. Both Wilde and the maenads understood this. Dionysus was called the liberator; his followers were outcasts — women, slaves, foreigners and unmasculine men. Dionysus freed these people from the bounds of their social status; gave them power, control, and pleasure, and for this the Roman senate condemned their rituals under penalty of death. Livy said that thousands were executed in the wake of the senate’s decree, but they did not succeed in the destruction of pleasure in their day, and neither did the British courts in Wilde’s. Christianity eventually supplanted Roman polytheism, but the joy and madness of Dionysus is still celebrated, and more than two thousand years after the Bacchanalia were outlawed in Rome, and his cult of decadence and pleasure was decimated, Dionysus’ earthly pleasures still abound.

Written by Michael (they/he).

Sources

Euripides. The Bacchae. Translated by Robin Robertson. Vintage Classics. 2014.

Kraemer, Ross S. ‘Ecstasy and Possession: The Attraction of Women to the Cult of Dionysus’ in The Harvard Theological Review, vol. 72, no. 1/2, pp. 55-80. 1979.

Livius (Livy), Titus. The History of Rome Book 39. Translated by Evan T. Sage. 1936. https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.02.0166%3Abook%3D39%3Achapter%3D1. Accessed 26 May 2024.

Walsh, P. G. ‘Making a Drama out of a Crisis: Livy on the Bacchanalia’ in Greece & Rome, vol. 43, no. 2, pp. 188-203. 1996.

Wilde, Oscar. The Uncensored Picture of Dorian Gray. Edited by Nicholas Frankel. Harvard University Press. 2012.Wilde, Oscar. The Picture of Dorian Gray. 3rd Norton Critical Edition. Edited by Michael Patrick Gillespie. W. W. Norton and Company, 2020.