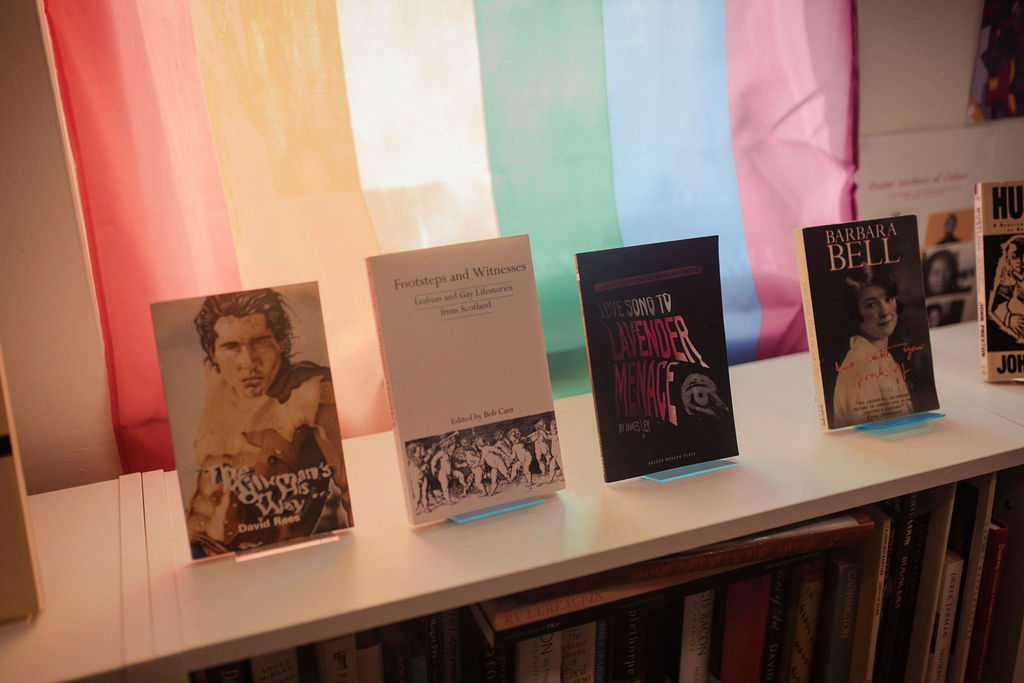

Lavender Menace volunteer archivist Ali Leetham takes us on a bona tour of London in this article.

Ever ordered a bevvy? Got into a barney? Or scarpered after telling a butch to naff off? Well, then you’re a Polari speaker.

This lexicon of slang terms is, for many, associated with camp comedians in the mid-twentieth century, such as the characters Julian and Sandy from the radio programme Round the Horne. Since then, Polari usage has dwindled, with the few people still familiar with it mostly comprising older gay men and theatrical performers.

Although many think of Polari as gay slang, historically it has had a diverse range of users from criminals, sailors, and sex workers to circus performers, wrestlers, and Punch and Judy men. So where did this language come from and how does it connect to these disparate communities?

To answer this, we’re going to take a bona (good) tour of London to visit the places and people who influenced Polari’s development. So let’s troll (walk) through the streets and vada (look at) the fantabulosa (fabulous) sites.

St Giles: A Den of Thieves

We begin our tour in the district of St Giles in the 16th and 17th centuries. Named after the patron saint of beggars and the poor, it may seem fitting that the district attracted a large vagrant and impoverished population. Foreigners ejected from the city by Elizabeth I also made their homes here, as did wealthy people who prized its ruralness and proximity to Westminster.

With this stark contrast between opulent houses and squalid slums, it is perhaps unsurprising that St Giles was one of the most proliferous sources of criminals hanged at the gallows at Tyburn1.

“Gin Lane” Hogarth’s depiction of the squalor and despair of a gin-addicted slum in St Giles, 1751. Tate.

This criminal underworld developed its own vocabulary, a slang language that speakers could use to conceal their meaning—and crimes—from mainstream ears. Thieves’ cant, also known as Pedlar’s French or St Giles Greek, largely covered terms useful to the criminal classes, such as types of criminals and victims, tools of the trade, and valuable items. But it included lots of everyday words, too.

A notable feature of cant is its use of compound terms to describe things according to what they do. For example, the word cheat (thing) is combined with verbs in many cant words such as smelling-cheat (nose) or bleating-cheat (sheep). Likewise, cove or cull/cully meaning man can be found in terms such as gentry cove (gentleman) or queer cull (fop).

Polari similarly combines words to make new, descriptive terms. Omi (man) is combined with charper (to search) in charpering omi (policeman), fake can be included in terms such as oglefakes (glasses), and queen can be prefixed to denote a particular type of gay man such as a drag queen2.

There is a little bit of overlap between cant and Polari. For example, ogles means eyes in Polari, and is assigned the same meaning in a cant dictionary written by ‘B.E.’ at the end of the 17th century. Also, gelt, originally from Yiddish, can be used to mean money in both languages3. Most cant words wouldn’t be familiar to a Polari speaker, though.

However, the charity and protest group The Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence adopted many cant words in their version of Polari in the late 20th century. A Polari version of the Bible, produced by the Manchester chapter of the sisterhood, includes numerous cant words, such as hearing cheats (ears) and cackle fart (egg)4.

Field Lane: Mother Clap’s Molly House

From St Giles, we head east to Holborn, to a narrow street called Field Lane. No longer in existence, Field Lane was the continuation of Saffron Hill and was immortalised in literature as the location of Fagin’s den. Oliver Twist wasn’t too impressed with the street, which he noted was lined with “little knots of houses, where drunken men and women were positively wallowing in filth; and from several of the door-ways, great ill-looking fellows were cautiously emerging, bound, to all appearance, on no very well-disposed or harmless errands.” 5

“Confirmation, or, the Bishop and the Soldier.” This satirical print appeared in 1822 after the Bishop of Clogher was discovered soliciting a soldier in a pub. Wikimedia Commons.

A century before Dickens was so disparaging of Field Lane, Margaret “Mother” Clap was the proprietress of one such den of iniquity. She ran one of the most popular molly houses in the 1720s.

Molly, or mollying cull, was the term most gay men used to refer to one another in the 18th century, and a molly house was a tavern or private house where they could drink and socialise. Mother Clap’s attracted many punters on a Sunday night due to its warm fire, abundance of spirits, and the fact there was a bed in every room.

An undercover constable who infiltrated Mother Clap’s in 1725 said he found there many men who “would sit on one another’s Laps, kissing in a lewd Manner, and using their Hands indecently. Then they would get up, Dance and make Curtsies, and mimic the voices of Women… Then they’d hug, and play, and toy, and go out by Couples into another Room on the same Floor, to be marry’d, as they call’d it.” 6

The “marrying” to which this charpering omi refers may, in many cases, have simply meant two mollies spending the night together in a room with a double bed. The marrying room at Mother Clap’s was attended by a man called Eccleston, who stood guard at the door if the couple wanted privacy, though some would prefer to leave the door open. Less common and more elaborate molly practices included mock births and masquerades involving drag.

The mollies’ vocabulary had a lot of crossover with criminals’ cant. Certainly, there was some overlap between the two subcultures: Saffron Hill was one of the major criminal areas at the time. And, after all, sodomy was a capital crime. Any mollies convicted of attempted sodomy would have made the acquaintance of criminals during their sojourns in prison.

The mollies introduced their own slang terms, too, some of which would be familiar to modern Polari speakers. For example, partners were known as trade (which makes sense as gay cruising grounds were called markets) and acquiring a partner was picking up. They also used playful epithets for each other such as ‘bold face’ and ‘saucy queen’.Another feature of the mollies’ language was the Female Dialect, which mostly consisted of Maiden Names for each other. Some of the mollies’ sobriquets came from their jobs, such as Dip-Candle Mary (a tallow chandler) and Orange Deb (an orange seller). Others had more intriguing derivations, like Susan Guzzle, Princess Seraphina, and Molly Soft-Buttocks6.

New Cut: Costermongers and Cheapjacks

Next, we travel due south across the Thames to find New Cut. Nowadays known simply as the Cut, this street runs from Waterloo Road in Lambeth to Blackfriars Road in Southwark. During the 1840s, New Cut was one of London’s busiest street markets (though not in the gay sense).

On a Saturday night, after workers had been paid for the week, we’d find a bustling scene at New Cut that excites all our senses. Gas lamps, grease lamps, candles, and stoves illuminate the market in various shades of white to red. Aromas of haddock and baked chestnuts mingle in the air. As women in shawls dawdle with baskets and small children weave their way through the crowds, we’re greeted with a cacophony of sounds. The calls of beggars clash with the ditties of street singers and the tunes of buskers. Above this din, 300 costermongers try to make themselves heard with calls such as “Three a penny Yarmouth bloaters” and “Chestnuts all ‘ot, a penny a score.” 7

“Sunday Morning in the New Cut, Lambeth.” Smith, Illustrated London News, 27 January 1872.

At New Cut, costermongers sold everything from meat, vegetables, and pies to boots, saucepans, and peep-show tickets. While they sold their wares to the public in plain English, between themselves they spoke their own slang language. It largely consisted of saying words backwards, sometimes adding or removing a letter or syllable. For costermongers, penny was yenep, halfpenny was flatch, and police was esclop7.

While these particular terms seem to have disappeared, some Polari terms have similarly been derived from backslang. For instance, Polari speakers would say riah for hair, esong for nose, and ecaf for face (often shortened to eek).

Unlike the costermongers who parked their handcarts at markets to sell their wares, cheapjacks were itinerant pedlars. Their vocabulary, known as grafter’s slang, had a broader range of influences, including Italian, Romany, and Cockney rhyming slang.

Philip Allingham’s 1934 book Cheapjack contained many grafter terms that Polari speakers would recognise. These included homey (man—usually omi in Polari), letty (lodgings—often latty in Polari), and bevvy (drink in both Polari and cheapjack slang)2.

The cheapjacks, and therefore the language they used, mingled with a variety of other itinerant classes, such as tramps, sex workers, actors, showmen, and circus folk.

Westminster Bridge Road: Putting on a Show

Talking of circus folk, the next stop on our tour is 225 Westminster Bridge Road. This was the site of Astley’s Amphitheatre, though it changed hands and names many times throughout the 18th and 19th centuries and was burned down and rebuilt on a few occasions.

Astley’s, Mr Pablo Fanque, and his trained Steed. Illustrated London News, 20 March 1847

Attending the circus there in 1846, we’d witness a spectacle that had never before been seen: an elephant balancing on a tightrope. There are bipedal performers, too—Newsome riding six horses at once, Plége the French rope dancer, Germani juggling oranges and knives on horseback. Many circus greats made their London debuts at Astley’s, such as celebrated equestrian Pablo Fanque who became Britain’s first black circus owner.

After the show, we can repair to Barnard’s Tavern opposite for refreshments, where two-thirds of the punters are circus and music hall artistes. As they imbibe, their chat is peppered with slang, some of which we recognise. Instead of ‘mate’ they say cully, which we already know links to 18th-century mollies and 17th-century criminals. And like the cheapjacks, the circus folk use letty. There are more terms with apparent connections to 20th-century Polari: bono (good—bona in Polari), dona (woman—dona or palone in Polari), and doing a Johnny Scaparey (to abscond—scarper in Polari)8.

Lexicographer Eric Partridge suggested that circus slang included lots of Romany and Cockney terms (as well as cant and Lingua Franca)9. While the extent of crossover between circus slang and Romany is unclear, it’s true that travelling circuses and Romany travellers could easily have crossed paths, providing an opportunity for cultural exchange.

A group that certainly did rub shoulders with the circus folk was theatrical performers. Actors were historically an itinerant and disparaged class10. And Thomas Frost, in his Circus Life and Circus Celebrities combines both groups in what he terms the ‘amusing classes’—‘actors, singers, dancers, equestrians, clowns, gymnasts, acrobats, jugglers, posturers’. In 1875, he tells us that three-quarters of these performers are concentrated within a couple of miles of Astley’s8.

This gives us one likely connection with the gay men still speaking Polari in the following century. The theatre has long been seen as a queer space by many. Back in the days of travelling troupes, actors were already seen as low-class and socially unacceptable, so they were likely more tolerant of queer people who didn’t fit into mainstream society.

And, of course, theatre stages have been an acceptable place for men to dress as women since the Renaissance when women were prohibited from acting. These camp antics were not just condoned by audiences but admired. In fact, a mile north of Astley’s is Drury Lane theatre where, in 1782, a bestubbled Charles Bannister in drag as Polly in The Beggar’s Opera caused so much hilarity that a poor Mrs Fitzherbert died of laughter two days later11.

Portrait of Charles Bannister (1738-1804), English actor and singer, en travesti as Polly Peachum in the Beggar’s Opera. James Sayers, ca. 1800-1825 National Portrait Gallery, London.

Incidentally, Bannister was given his start in London by playwright Samuel Foote, who was accused of homosexuality and was said to frequent a Moorfields pub two miles east of Drury Lane, next to a path infamously known as the Sodomites’ Walk6.

Eyre Place: The Organ-Grinders’ Colony

Next, we’ll return to the district of Holborn, though we’ll find the demographics much changed since our last visit in the 1720s. Over the 19th century, thousands of Italians moved to Great Britain, with roughly half of them making their home in London. Specifically, we’ll pay a visit to Eyre Place in the heart of Holborn’s Italian Quarter.

The Times published an article in 1864 titled ‘An Organ-Grinders’ Colony’ that attacked the “chief colonies of the Italian organ-grinders” for their sanitary conditions and overcrowding. “In Eyre-place”, the article ran, “it was lately found that as many as fourteen organ-grinders slept in one room, and, not content with that, beds were made up on the staircases.” According to the police, such lodging houses would also contain monkeys in boxes and white mice on the landings12.

The organs were of various sizes and mechanisms, being carried or wheeled through the streets, comprising pipes or metal reeds, some even having mechanical figures to boot. Turning a handle would play one of the organ’s set number of tunes. Some organ men had a monkey they trained to grind the organ or perform other tricks13.

Italian immigrants in this line of work had an organised system where multiple organ grinders would be in the employ of a padrone (master) who’d provide them lodgings, food, and an organ in return for half their earnings. Many grinders would save the other half until they could afford to buy their own organ and go independent, sometimes then bringing over more Italian immigrants and becoming padroni themselves12.

This cartoon illustrated the views of many in the middle class who disparaged organ grinders and Italian immigrants. John Leech, Punch, volume 27, 1854.

While organ grinding was the most popular profession for Italian immigrants, they found other kinds of work, too. Victorian journalist Henry Mayhew interviewed several Italian ‘Street Folk’, including a man whose dogs danced in little outfits and another who exhibited mechanical figures, such as a little Judith who robotically beheaded Holofernes on repeat7.

What all these people had in common was that they were itinerant. Performers would wander the streets, or even the country, in search of an audience. In this way, they would certainly have mixed and talked with other itinerant classes, transmitting bits of their language.

Another type of performance originally introduced by Italian immigrants was Punch and Judy shows, and the Italian influence was still strong once Brits started taking on the work instead. Mayhew interviewed a Punchman who, though English, explained how the slang language he used with other Punchmen was a ‘broken Italian’. It included words such as bonar (good), munjare (food), and vardring (looking)7—words that would all still be in use as Polari in the 20th century (give or take some spelling variations).

In fact, a significant section of the Polari lexicon has Italian derivations. For a start, numbers in Polari are phonetic and slightly anglicised spellings of Italian numbers. When linguist Ian Hancock collated a list of Romance-derived Polari terms in the 1980s, he suggested potential Italian etymologies for well over half of them14.

The Docklands: Sea Queens and Drag Queens

We now turn our attention to the East End of London. Some have made a distinction between theatre-influenced West End Polari and the East End version which is more rooted in Yiddish, Cockney, and sea queens.

Seafarers have picked up lots of new words through their travels. Since the Crusades, many sailors travelling through the Mediterranean have used Lingua Franca, which mixes languages such as Italian, French, Greek, Arabic, and Spanish. A few of these terms would be fairly familiar to Polari users, such as bona (good/well) and mangia (food). Sailors would also have ample opportunity to transmit these words to other itinerant classes as they’d often have to walk a long way from the port to their home or pay, perhaps turning to begging, crime or working as a cheapjack to get by2.

Sailors in drag on S.S. Caronia, 1950s, The James Gardiner Collection, Wellcome Collection 2045317i

By the mid-twentieth century, the Merchant Navy attracted many gay men who wanted to trade the oppressive atmosphere of the UK for a sense of freedom and adventure. Drag queen Lorri Lee joined the Merchant Navy by accident after following two handsome men into what he thought was a club but turned out to be a shipping office15.

Merchant ships provided an opportunity for gay crew members to entertain each other with drag shows, find husbands, and gossip about them in Polari. The sea queens even created new terms such as fruit locker (a cabin full of gay men) and trade curtain (the curtain on a bunk that could be pulled across for privacy when having sex in a shared cabin)16.

A number of pubs in the London docks were popular with both local gay men and seafarers who’d put into port. These included The Ken, The Roundhouse and the Marquis of Granby, which put on drag shows. Lorri Lee recalled how the local East End queens would do their hair and don their best outfits whenever a ship was coming in16.

The queens who managed to pick up some seaweed (a sailor) at the pub might continue their night by heading to a house in Silvertown on the north bank of the Thames. The house belonged to Stella Minge, a former member of the Merchant Navy who threw parties on a Friday night that wouldn’t finish until Sunday or Monday. Stella’s also attracted many policemen—either to attend to the frequent noise complaints or just to join the party17.

Paris Theatre: Julian and Sandy

For the final stop on our bona tour, we’re heading all the way over to the West End, to the Paris Theatre at 12 Lower Regent Street. Originally a cinema, it was converted into a recording studio by the BBC and provided an intimate location to tape radio comedies in front of an audience of up to 400.

This was where Kenneth Horne recorded his hit radio show Round the Horne before broadcasting it to 15 million listeners between 1965 and 1968. Two of the most popular characters on the show were the camp, out-of-work actors Julian and Sandy, named after the gay musical writers Julian Slade (Salad Days) and Sandy Wilson (The Boy Friend)18.

They were played by queer actors Hugh Paddick and Kenneth Williams, and their sketches involved the sensible, establishment figure of Mr Horne running into the pair in increasingly unlikely temp jobs while they were “resting” (unemployed) from acting.

The most striking feature of the sketches was Julian’s and Sandy’s extensive use of Polari slang. This provided an in-joke for queer and theatrical listeners who understood Polari, while millions of other listeners found the characters hilariously risqué without being sure exactly what they were saying.

Most sketches would feature the classic greeting of: “How bona to vada your dolly old eek” (How nice to see your pretty face). In one, Kenneth Horne visits a new publishing firm:

Kenneth: Hello? Anybody there?

Hugh: Oh hello. I’m Julian and this is my friend Sandy.

Ken W: We’re Bona Books. We’re just filling in as book publishers. Normally, if you’ll forgive the expression, we’re actors by trade.

Hugh: But trade’s been a bit rough lately, so we’ve had to take whatever we can get19

Trade means sex or sexual partners, and rough trade tends to refer to rough or casual sex, often with a stranger or sex worker. Double entendres like this were a fixture of the sketches. Their innocent alternative meaning, along with the incomprehensibility of Polari language for most listeners, meant that the programme got away with making the characters obviously but unspokenly gay in a time when sex between men was still illegal.

The affection the camp characters inspired across the nation may have contributed to the changing attitudes that resulted in the partial decriminalisation of homosexuality in 196720. But while Round the Horne marked a peak in the number of people exposed to Polari, the lexicon’s actual usage was declining.

Hugh Paddick, Kenneth Williams and Kenneth Horne, 1965-68, BBC

Round the Horne, 1965-68, BBC Light Programme

Beyond London

Although Polari hasn’t been used much since the 1960s, it didn’t vanish completely. Some Polari words made the leap into mainstream slang. Most people—gay or straight—know what cottaging means nowadays. Camp and drag have become common parlance. And many use carsey, manky or rozzers with no idea of their queer origins. Princess Anne was even alleged to have told reporters to “Naff off”, though it’s unlikely she’d have been aware of the word’s queer meaning of “Not Available For F***ing”.

The global order of queer and trans nuns, the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence, was founded in San Francisco in 1979. The activist group has been involved with many activities, from AIDS education to mock exorcisms to hosting the minute’s silence and minute’s noise at Edinburgh Pride. They’ve also revived the Polari language for use in their ceremonies.

When the Sisters canonised gay filmmaker Derek Jarman in 1991, they addressed the crowd with: “Sissies and Omies and palonies of the Gathered Faithful, we’re now getting to the kernel, the nub, the very thrust of why we’re gathered here today at Derek’s bona bijou lattie.” 21

Letter from the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence to Lavender Menace co-founder Bob Orr. Treasures exhibition, 2024, National Library of Scotland.

The year before this, Morrissey referenced Polari in his song Piccadilly Palare from the album Bona Drag.

You’ll find echoes of and nods to Polari all over the place. The Polari Literary Salon was founded in 2007 and established the Polari Prize for LGBTQ+ books. The language has inspired the names of varied businesses and organisations: Café Polari is a queer social space in the Scottish Borders; VADA is an LGBTQ community theatre company in northwest England; and Bona Togs was a fashion store on the island of Jersey22. The former Shoreditch restaurant Hoi Polloi even had an entire Polari-inspired cocktail menu offering concoctions such as Cod Eek (bad face) and National Handbag (dole/welfare)23.

This phrase, meaning “He’s not very well endowed”, was projected onto the side of Bury’s Art Museum as part of an art project. Bury Light Night, 2012. Babelzine.

The 21st century has seen the occasional attempt at revival—or at least education. The short-lived Polari Lounge in Stoke-on-Trent was a queer cafe that provided pamphlets on Polari2. Also, in 2004, legendary Soho nightclub Madame Jojo’s taught its staff to use Polari at work24.

More recently, filmmakers Brian and Karl created a short film that imagined a Polari conversation between two men in the 1960s. A couple of years later, a Cambridge theological college marked LGBT history month with a church service given in Polari. But they were forced to apologise after some took offence at the Fantabulosa fairy prayer and a reference to God as “O Duchess, my butchness”25.

Putting on the Dish, 2015, Brian and Karl

These activities have met with varying reactions and levels of success. But the many references and revival attempts suggest that while Polari is generally considered a dead language, interest in it is still very much alive. There’s something about a secret queer language—one that connects history, diverse communities and activism—that can inspire passion in any age.If you’d like to learn to polari bona, then why not troll on down to the Lavender Menace archive to vada our Polari dictionary, Fantabulosa?

Article by Ali Leetham, writer and volunteer archivist.

References

- Ackroyd, P. (2000). London: The Biography. Chatto & Windus.

- Baker, P. (2020). Fabulosa! The Story of Polari, Britain’s Secret Gay Language. Reaktion Books.

- Beier, L. (1995). Anti-language or jargon? Canting in the English underworld in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. In P. Burke & R. Porter (Eds.), Languages and Jargons: Contributions to a Social Hisstory of Language (pp. 64-101). Wiley.

- Smith, B. (2015). Polari Bible (7th ed.). https://archive.org/details/polari-bible/page/966/mode/2up

- Dickens, C. (1994). Oliver Twist. Penguin.

- Norton, R. (1992). Mother Clap’s molly house: the gay subculture in England, 1700-1830. GMP.

- Mayhew, H. (1949). Mayhew’s London (P. Quennell, Ed.). The Pilot Press.

- Frost, T. (1875). Circus life and circus celebrities. Tinsley Brothers. https://www-victorianpopularculture-amdigital-co-uk.eux.idm.oclc.org/Documents/Details/NFA_FROS_1981?SessionExpired=True

- Partridge, E. (1954). Slang to-day and yesterday. Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Partridge, E. (1950). Here, there and everywhere. Hamish Hamilton.

- Obituary of considerable Persons, and Promotions. (1782). The Gentlemen’s Magazine, 52, 207. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015013465862&seq=221

- Sponza, L. (1988). Italian Immigrants in Nineteenth-century Britain: Realities and Images. Leicester University Press.

- Smith, C. M. (1857). Music Grinders of the Metropolis. In Curiosities of London Life (pp. 1-18). London, W. and F. G. Cash. https://www.victorianlondon.org/publications/curiosities-1.htm

- Hancock, I. (1984). Shelta and Polari. In P. Trudgill (Ed.), Language in the British Isles (pp. 384-403). Cambridge University Press.

- Lee, L. (Performer). (1981). Bona Queen Of Fabularity [Film]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u-iHfJTLgtg&t=2s&ab_channel=sweetsandnuts

- Baker, P., & Stanley, J. (2003). Hello Sailor! : The Hidden History of Gay Life at Sea. Taylor & Francis Group.

- Stella Minge (192?–?) sailor, bawdy house keeper. (2013, March 5). A Gender Variance Who’s Who. Retrieved January 18, 2025, from https://zagria.blogspot.com/2013/03/stella-minge-192-sailor-bawdy-house.html

- Dixon, S. (2000, November 13). Hugh Paddick Obituary. The Guardian.

- Took, B. (1998). Round the Horne: The Complete and Utter History. Boxtree.

- Morrison, R. (1998, July 24). Oh bold, very bold – and wonderful. The Times, 33.

- Lucas, I. (1997). The Color Of His Eyes: Polari and the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence. In Queerly Phrased: Language, Gender, and Sexuality (pp. 85-94). Oxford Academic. https://academic.oup.com/book/48447/chapter-abstract/421391574?redirectedFrom=fulltext

- The shop ‘Bona Togs’ closes after 40 years trading. (2008). Jersey Evening Post. https://catalogue.jerseyheritage.org/collection-search/?si_elastic_detail=archive_110228992

- Rayner, J. (2014, March 2). Hoi Polloi: restaurant review | Scandinavian food and drink. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2014/mar/02/hoi-polloi-restaurant-review-jay-rayner

- ‘Fabulosa’ lingo revived at club. (2004, December 6). BBC. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/england/london/4071811.stm

- Sherwood, H. (2017, February 3). C of E college apologises for students’ attempt to ‘queer evening prayer’. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/feb/03/church-of-england-college-apologises-students-queer-evening-prayer