Lavender Menace volunteer Ali Leetham reviews Queer As Folklore by Sacha Coward

Sacha Coward’s debut book, Queer As Folklore, is dedicated “to every person who has ever walked around a museum and wondered if they belong there.” Physical spaces, especially ones created by those in power, aren’t always representative of or welcoming to LGBTQ+ people.

“I started to see that I loved the museums but they didn’t love me back,” Coward explained. He’s worked in the museum sector for 15 years but realised that he often wasn’t represented in them. “You know, me lusting after Harry Appleby on sportsday—that wasn’t in the ancient Greek gallery, which is really funny if you know anything about ancient Greece.”

But stories—stories are where we can find understanding, connection, and meaning. Magical escapism or a mirror held up to society. Stories flourish in the margins; naturally, they’re where the marginalised flourish. Now, more than ever, there seems to be a queer appetite for all things folklore and mythology.

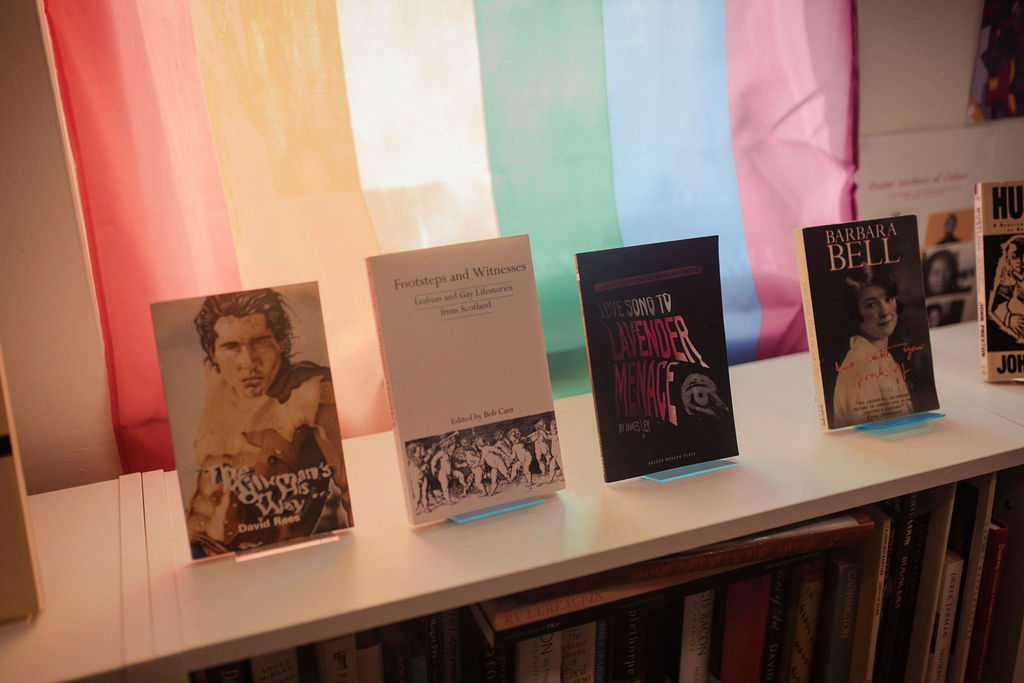

Recent years have seen a glut of books published on queer myths and folk tales. Here at Lavender Menace, we hosted a sold-out Queer as Folklore event last year where Ellen Galford and Rachel Plummer discussed the role of Scottish folklore in their work. So what is it that’s drawing so many LGBTQ+ people to create and consume folklore? This is the question at the heart of Sacha Coward’s new book.

One thing the book makes clear is that this is not a new phenomenon. From the homoromantic relationship at the heart of the 4,000-year-old Epic of Gilgamesh to Callisto’s sapphic love for Artemis in ancient Greek myth to cross-dressing Norse gods: Folklore has always been queer.

Coward takes us on a rollicking romp through time and space, pausing to introduce us to homoerotic heroes, bisexual beasts, and gender-bending priestesses. And he by no means limits himself to the Western canon. We’re also immersed in Japanese folklore, where mischievous fox spirits possess or impersonate the opposite sex. In Malian mythology, hermaphroditic ancestral spirits known as Nommo brought people wisdom. And in Indigenous South American cultures, Sirinx, the nonbinary Godx of music, has some parallels with the European conception of mermaids.

The book is divided into five parts, each exploring a different corner of the folkloric universe. The first two deal with beings most commonly associated with classic folklore. It all begins with a menagerie of magical creatures. Starting with his childhood obsession with Disney’s Ursula (who was based on the drag queen Divine), Coward investigates mermaid myths from around the world. We then get the horn with talk of unicorns. And after a brief digression into ancient dildos made of animal horns, the first part finishes on faeries, with reference to lesbian actress Maude Adams who set the stage for women to cross-dress as Peter Pan.

The second part deals with shapeshifters and cursed beings. Here, Coward links werewolves and animal transformation with communities associated with the modern LGBTQ+ spectrum, such as bears and furries. He also charts the queer ancestry of vampires. Lilith—who in Jewish demonology refused to sleep with Adam and became the mother of vampires—could be read as gay or asexual. Centuries later, the mad, bad, and bisexual Lord Byron became the model for the modern suave and sophisticated archetype through his depiction in the novella The Vampyre.

Things get wyrd and witchy in Part 3 as the book delves into both past queer women accused of witchcraft and the present preponderance of LGBTQ+ people who follow Neopagan religions. There’s also a descent into the depths of devil worship and occultism as Coward lifts the veil from Aleister Crowley’s bisexual ‘magick’ orgies and the medieval lesbian nun thought to have demonic visitations. One of my favourite parts of the book is the chapter on ghosts and spirits, where we learn that the otherwise prudish Victorians were entranced by seances where female mediums might tie themselves together on a mattress, disrobe for inspection by a female guest, or expel ectoplasm from their vaginas.

The fourth part of the book expands the folklore universe to include more contemporary stories, such as tales of robots and aliens. But these ideas might not be as modern as we think. As Coward illustrates, Hephaestus created automatons in ancient Greek mythology and Lucian wrote in the first century about a race of gay aliens who lived on the moon. Another of my personal highlights is where we meet notorious real-life pirates Anne Bonny and Mary Read who dressed as men in order to lead lives of swash-buckling adventure. Then in a rumination on superheroes, Coward draws a direct queer lineage from the ancient homoromantic heroes of Gilgamesh and Achilles to modern-day superheroes with their secret identities and camp costumes.

The fifth and final part of the book ties everything together with a mix of research and speculation about what makes folklore quintessentially queer.

Coward drew on a cornucopia of different sources for his research. These run the gamut from cuneiform tablets, the Viking Edda, and medieval bestiaries to slash fiction, video games, and Filipino rap. An invaluable resource for any foray into folklore is people. Coward’s interviews with diverse contributors such as an Indigenous performer, a gay comic-book artist, and a sword lesbian historian add extra layers of meaning and insight to the tales told. The author even turned to X users to shine a light on the modern significance of witches to the LGBTQ+ community.

Despite the huge amount of in-depth research, Queer as Folklore is very accessible. It’s incredibly informative without being dry or overly academic. Coward’s passion for and knowledge of his subject shines through, but you’ll find a smattering of footnotes to explain terms such as kink, Sodom, and Praemonstratrix to the uninitiated.

The book is something of a whistlestop tour as it covers such a breadth of creatures and characters. There’s so much to cover that it felt like each chapter could be made into a whole book. When I asked Coward about how he decided which chapters to include, he explained he searched for obvious queer hooks, for stories and characters we could grab hold of. “I wanted it to be almost like a Pokédex, with each chapter being the archetype of a creature.”

The text is also punctuated by images. The start of each new part is heralded by a gorgeously unsettling and otherworldly illustration of some liminal hybrid being. There are also images within chapters to add visual context, such as a photo of sailors in drag, a doodle by Aleister Crowley of an erect demon, and a 17th-century depiction of a scaled galloping Lamia with human breasts and a clawed penis.

Researching and writing Queer As Folklore had a marked effect on Coward. “Seeing the stories of thousands of years, my queerness doesn’t just feel like this little thing that exists in me. It now feels like this epic human story that I’m woven into, and I feel passionate about sharing that and being part of that.” He hopes readers will also feel a part of this shared lineage. The book ends with a challenge to today’s creators to invent and reinvent stories for the queer generations of the future.

Review by Ali Leetham

Lavender Links

At Lavender Menace, we love to find connections between new releases and the older titles on our archive shelves. Whenever we review a new book on the blog, we’ll be pairing it with a book from the archive. We might choose Lavender Links based on genre, setting, characters or just the general vibe!

Is there another book that Queer as Folklore reminds you of? Let us know in the comments!

Queer as Folklore’s Lavender Link…

Feminist Fables by Suniti Namjoshi

Why we chose this book: Both Queer as Folklore and Feminist Fables subvert the normal rules and readings of fables, folklore, and fairy tales. While Coward delves into the queer histories and contexts of folklore, Namjoshi imagines new tales from a feminist perspective.