Category: Archive

-

Book Review: Waiting on a Friend by Natalie Adler

Lavender Menace volunteer Katie Marson reviews Waiting on a Friend by Natalie Adler, which will be published by Quercus Publishing later this year. Natalie Adler’s Waiting on a Friend is […]

-

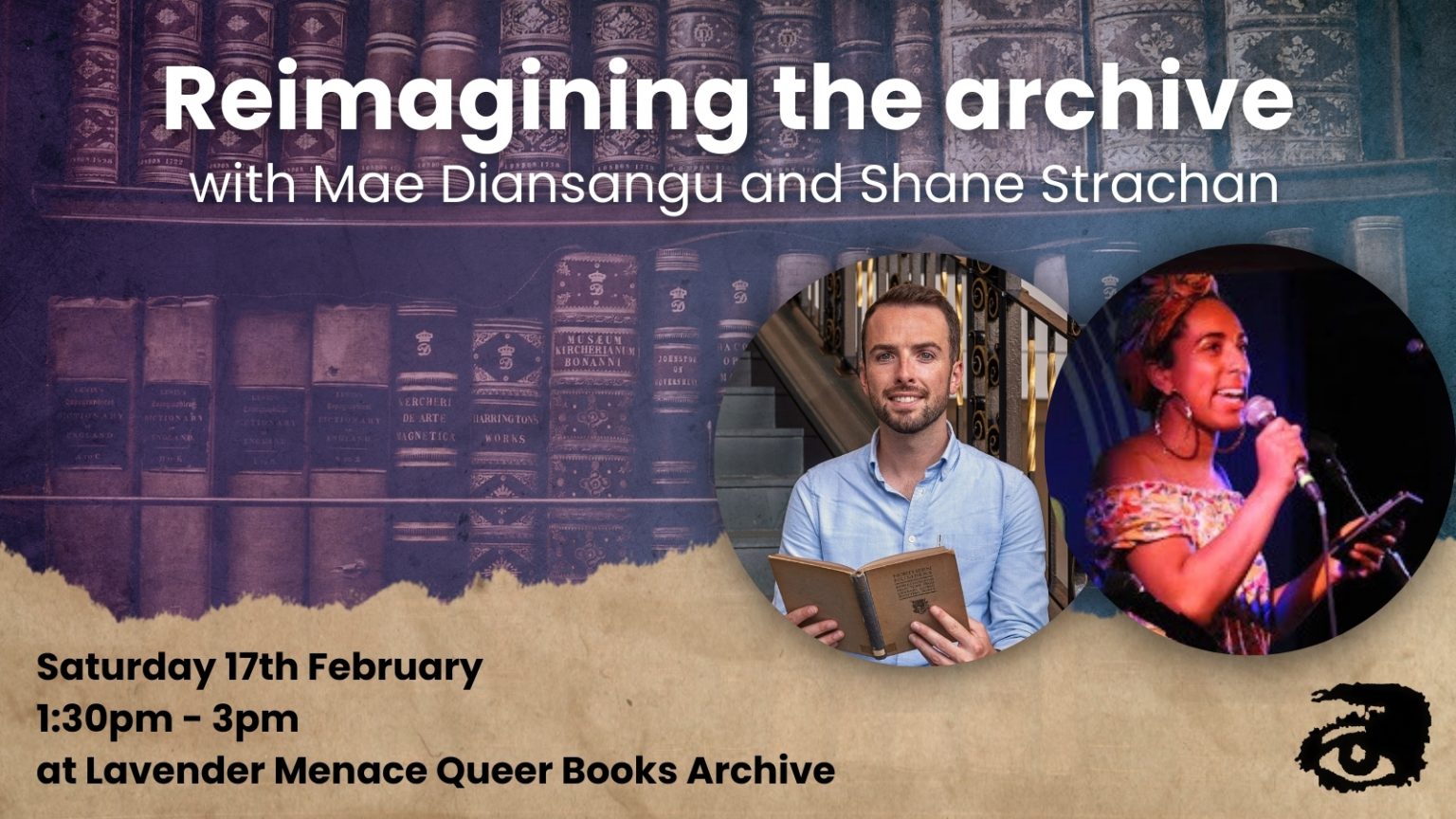

Reimagining the Archive with Mae Diansangu and Shane Strachan

You can now watch the recording of this event online Last year, we welcomed Mae Diansangu and Shane Strachan to the Lavender Menace Queer Books Archive for an afternoon of […]

-

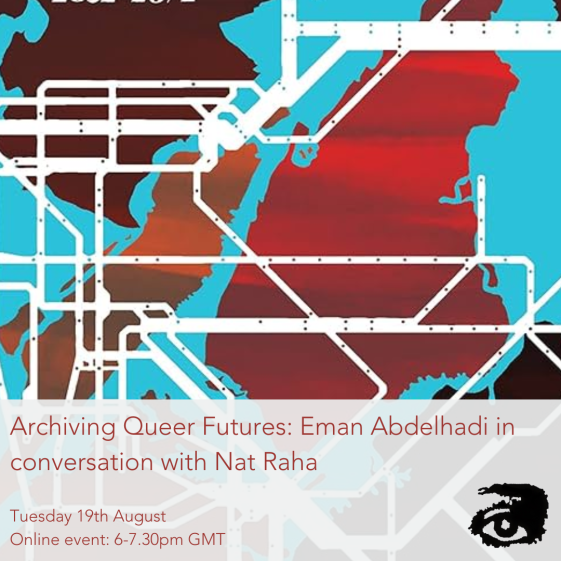

Archiving Queer Futures: Eman Abdelhadi in conversation with Nat Raha

You can now watch the recording of this event online. Lavender Menace hosted an online discussion between two activist scholars on imagining and archiving queer futures. Dr Eman Abdelhadi is […]

-

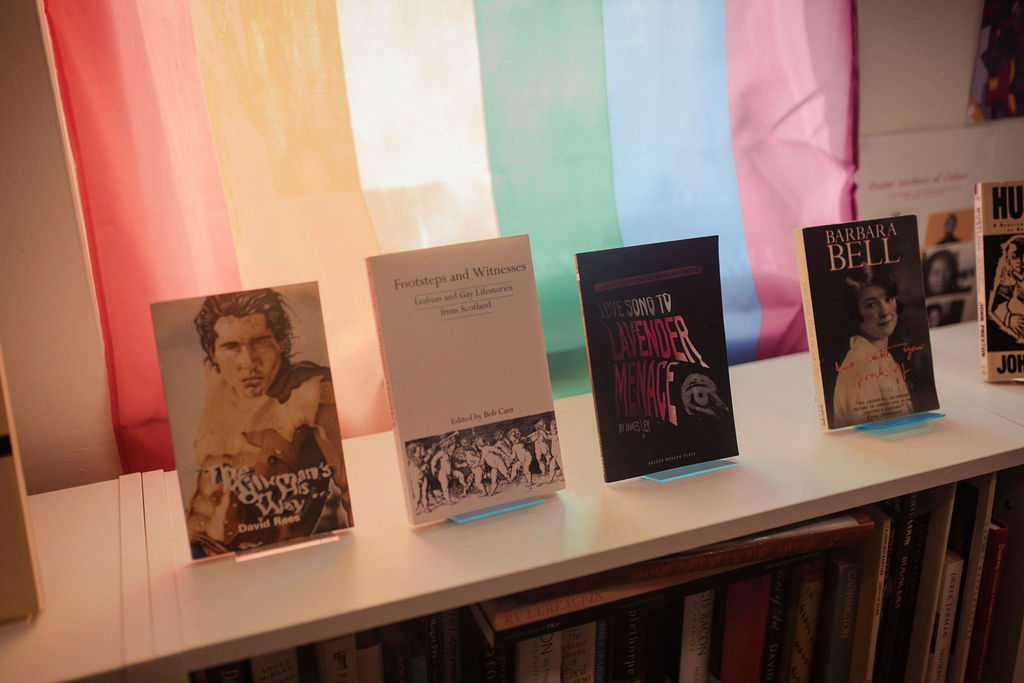

We want your books

Lavender Menace’s queer books archive is growing. We are cataloguing several recent donations, including one from LGBT Health and Wellbeing, and making some exciting finds. We’re always looking for out […]

-

Rebecca by Daphine du Maurier

Rebecca by Daphne du Maurier.Gollancz, 1938; Virago (present publisher). Last night I dreamt I went to Manderley again… Rebecca, Daphne du Maurier’s best known novel, has never been out of […]